- Home

- Larry Niven

01-Human Space

01-Human Space Read online

The KNOWN SPACE Universe

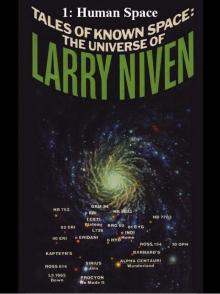

Tales of Known Space 1: Human Space

World of Ptavvs

Flatlander (Gil Hamilton)

Protector

A Gift From Earth

Tales of Known Space 2: Known Space

Crashlander (Beowulf Shaeffer)

Ringworld

Ringworld Engineers

The Ringworld Throne

Ringworld's Children

Fleet of Worlds

Juggler of Worlds

Destroyer of Worlds

Betrayer of Worlds

Fate of Worlds

The Man-Kzin Wars

TALES OF NEW SPACE

Del Rey 1985

The Coldest Place

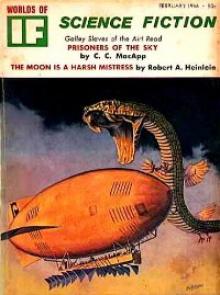

Worlds of If, December 1964

Becalmed in Hell

The Magazine of F & SF, February 1965

Eye of an Octopus

Galaxy Magazine, February 1966

How the Heroes Die

Galaxy Magazine, October 1966

At the Bottom of a Hole

Galaxy Magazine, December 1966

The Jigsaw Man

Dangerous Visions, Harlan Ellison (ed) 1967

Intent to Deceive [“The Deceivers”]

Galaxy Magazine, April 1968

Wait It Out

The Future Unbound Program Book, 1968

Cloak of Anarchy

Analog SF March 1972

Introduction, Afterthoughts & Bibliography

updated versions from

Three Books of Known Space, Del Rey, 1996

Cover Art by Rick Sternbach

Contents

Timeline for Known Space

Introduction:

My Universe and Welcome to It!

The Coldest Place

Becalmed in Hell

Wait It Out

Eye of an Octopus

How the Heroes Die

The Jigsaw Man

02-World of Ptavvs

At the Bottom of a Hole

Intent to Deceive

Cloak of Anarchy

Afterthoughts

Magazine artwork

Rick Sternbach's Map of KNOWN SPACE

Bibliography: The Worlds of Larry Niven

Introduction:

My Universe and Welcome to It!

Thirty-two years ago I started writing. Thirty-one years ago I started selling what I wrote. And thirty-one years ago I started a future history—the history of Known Space.

Known Space now spans a thousand years of future history, with data on conditions up to a billion and a half years in the past. Most of the stories take place either in Human Space (the human-colonized worlds and the space between, a bubble sixty light-years across by Louis Wu's time) or in Known Space (the much larger bubble of space explored by human-built ships but controlled by other species), but arms of exploration reach 200 light-years up along galactic north and 33,000 light-years to the galactic core.

The series now includes six novels (including the brand-new The Ringworld Throne) plus the stories in Flatlander (Gil the Arm's tales) and Crashlander (the stories of Beowulf Shaeffer) and the stories you're holding now, plus eight volumes of stories set during the period of the Man-Kzin Wars and written by other authors. See the updated Timeline for details.

Future histories tend to be chaotic. They grow from a common base, from individual stories with common assumptions, but each story must—to be fair to readers—stand by itself. The future history chronicled in the Known Space series is as chaotic as real history is. Even the styles vary in these stories, because my writing skills have evolved over eleven years of real time.

But this is the book with the crib sheets. These stories, including two novels, are published in chronological order. I've scattered supplementary notes between them to explain what is going on between and around the individual novels and stories in a region small on the galactic scale but huge in terms of human experience.

A few general notes are in order here:

1. The tales of Gil the Arm are missing. Gil's career hits its high point around A.D. 2121, between World of Ptavvs and Protector. His stories appear all together in the collection called Flatlander.

2. I dithered over including certain stories. "The Coldest Place" was. obsolete before it reached print. That story and "Eye of an Octopus" show the hand of the amateur. But these stories are part of the fabric of Known Space, so they're here. And Mercury rotates once per solar orbit—in Known Space but not in the real universe!

3. You may feel that Mars itself is changing as you read through the book. Right you are. "Eye of an Octopus" is set on pre-Mariner Mars. Mariner IV's photographs of the craters on Mars sparked "How the Heroes Die." Sometime later, an article in Analog shaped the new view of the planet in "At the Bottom of a Hole." If the space probes keep redesigning our planets, what can we do but write new stories? Mars continues to change, and I should be keeping up. But the field is seething with recent Mars stories. If the best writers in the field insist on writing my stories for me, what can I offer but gratitude?

4. I was sorely tempted to rewrite some of the older, clumsier stories. But how would I have known where to stop? You would then have been reading updated stories with the facts changed around. I've assumed that that isn't what you're after. I hope I'm right.

5. The Tales of Known Space cluster around six eras. First there is the near future, the exploration of interplanetary space during the next quarter century.

There is the era of Lucas Garner and Gil "the Arm" Hamilton: A.D. 2106-2130. Interplanetary civilization has loosened its ties with Earth, has taken on a character of its own. Other stellar systems are being explored and settled. The organ bank problem is at its sociological worst on Earth. The existence of nonhuman intelligence has become obtrusively plain; humanity must adjust.

There is an intermediate era centering around A.D. 2340. In Sol system it is a period of peace and prosperity. On colony worlds such as Plateau times are turbulent. At the edge of Sol system a creature that used to be Jack Brennan fights a lone war. The era of peace begins with the subtle interventions of the Brennan-monster (see Protector); it ends in contact with the Kzinti Empire.

The tales of the Man-Kzin Wars have been written mostly by others. It still amazes me that I could get these masters to play in my universe instead of their own. From them I've learned more about kzinti family life, intelligent female carnivores, esoteric cosmology, and military maneuverings than I ever guessed was there. Poul Anderson gives us ancient worlds covered in natural plastics and bucky-balls (now "fullerenes"). Pournelle and Sterling did aerobraking through a sun, using a stasis field. Benford and Martin expanded the Known Space cosmology beyond this universe. Donald Kingsbury's cowardly Kzin is beyond this universe. Donald Kingsbury's cowardly Kzin is scary as hell. A kzinti scout died in India in Kipling's time, a notch short of bringing the Patriarchy to Earth.

The fourth period, following the Man-Kzin Wars, covers part of the twenty-sixth century A.D. It is a time of easy tourism and interspecies trade in which the human species neither rules nor is ruled. New planets have been settled, some of which were wrested from the Kzinti Empire during the wars.

The fifth period resembles the fourth. Little has changed in two hundred years, at least on the surface. The thruster drive has replaced the less efficient fusion drives, and a new species has joined the community of worlds. But there is one fundamental change: the Teela Brown gene—the "ultimate psychic power"—spreading through humanity. The teelas have been bred for luck.

It always seems that I have more to say about Known Space.

Teela Brown was bred for luck. Or else she's a fluke of statistics, no more remarkable than any lottery winner. How can you tell? Teela's luck has some amaz

ing implications, and it took me twenty-five years to find them.

Characters more intelligent than the author are the greatest challenge an author can face, and the Ringworld is crawling with them. They're called "protectors." Strangers around the globe keep telling me things I didn't know about the Ringworld's structure, and I've found a few of my own. I've been playing games of anthropology across habitable land three million times the surface area of the Earth.

But a fundamental change in human nature —and the teelas are that—makes life difficult for a writer. The period following Ringworld might be pleasant to live in, but it is short of interesting disasters. Only one story survives from this period—"Safe at Any Speed"—a kind of advertisement. There will be no others.

There is something about future histories, and Known Space in particular, that gets to people. They start worrying about the facts, the mathematics, the chronology. They work out elaborate charts or program their computers for close-approach orbits around point masses. They send me maps of Human, kzinti, and Kdatlyno space; dynamic analyses of the Ringworld; ten-thousand-word plot outlines for the novel that will wrap it all into a bundle; and treatises on the Grog problem. To all of you who have thus entertained me and stroked my ego, thanks.

The chronology in this book is the work of decades on the part of a whole army of people.

Tim Kyger, Spike MacPhee, and Jerry Boyajian got involved in the 1970s. I've updated it.

John Hewitt did the research that shaped Chaosium's tabletop Ringworld game. He did that by bracing me at conventions and demanding that I make decisions: conflicting dates, shapes for tools and weapons, explanations and descriptions. His work "hardened" Known Space. He later helped me find the pages I needed to form a bible for the Man-Kzin Wars authors, and Jim Baen and I have been using it ever since.

The Guide to Larry Niven's Ringworld, by Kevin Stein, is a guide to all of Known Space. I've found it more accurate than my fallible memory.

—Larry Niven

Tarzana, California

September 1995

The Coldest Place

In the coldest place in the solar system, I hesitated outside the ship for a moment. It was too dark out there. I fought an urge to stay close by the ship, by the comfortable ungainly bulk of warm metal which held the warm bright Earth inside it.

“See anything?” asked Eric.

“No, of course not. It’s too hot here anyway, what with heat radiation from the ship. You remember the way they scattered away from the probe.”

“Yeah. Look, you want me to hold your hand or something? Go.”

I sighed and started off, with the heavy collector bouncing gently on my shoulder. I bounced too. The spikes on my boots kept me from sliding.

I walked up the side of the wide, shallow crater the ship had created by vaporizing the layered air all the way down to the water ice level. Crags rose about me, masses of frozen gas with smooth, rounded edges. They gleamed soft white where the light from my headlamp touched them. Elsewhere all was as black as eternity. Brilliant stars shone above the soft crags; but the light made no impression on the black land. The ship got smaller and darker and disappeared.

There was supposed to be life here. Nobody had even tried to guess what it might be like. Two years ago the Messenger VI probe had moved into close orbit about the planet and then landed about here, partly to find out if the cap of frozen gasses might be inflammable. In the field of view of the camera during the landing, things like shadows had wriggled across the, snow and out of the light thrown by the probe. The films had shown it beautifully. Naturally some wise ones had suggested that they were only shadows.

I’d seen the films. I knew better. There was life.

Something alive, that hated light Something out there in the dark. Something huge… “Eric, you there?”

“Where would I go?” he mocked me.

“Well,” said I, “if I watched every word I spoke I’d never get anything said.” All the same, I had been tactless. Eric had had a bad accident once, very bad. He wouldn’t be going anywhere unless the ship went along.

“Touché,” said Eric.

“Are you getting much heat leakage from your suit?”

“Very little.” In fact, the frozen air didn’t even melt under the pressure of my boots.

“They might be avoiding even that little. Or they might be afraid of your light.” He knew I hadn’t seen anything; he was looking through a peeper in the top of my helmet.

“Okay, I’ll climb that mountain and turn it off for awhile.”

I swung my head so he could see the mound I meant, then started up it. It was good exercise, and no strain in the low gravity. I could jump almost as high as on the Moon, without fear of a rock’s edge tearing my suit. It was all packed snow, with vacuum between the flakes.

My imagination started working again when I reached the top. There was black all around; the world was black with cold. I turned off the light and the world disappeared.

I pushed a trigger on the side of my helmet and my helmet put the stem of a pipe in my mouth. The air renewer sucked air-and smoke down past my chin. They make wonderful suits nowadays. I sat and smoked, waiting, shivering with the knowledge of the cold. Finally I realized I was sweating. The suit was almost too well insulated.

Our ion-drive section came over the horizon, a brilliant star moving very fast, and disappeared as it hit the planet’s shadow. Time was passing. The charge, in my pipe burned out and I dumped it.

“Try the light,” said Eric.

I got up and turned the headlamp on high. The light spread for a mile around; a white fairy landscape sprang to life, a winter wonderland doubled in spades. I did a slow pirouette, looking, looking … and saw it.

Even this close it looked like a shadow. It also looked like a very flat, monstrously large amoeba, or like a pool of oil running across the ice. Uphill it ran, flowing slowly and painfully up the side of a nitrogen mountain, trying desperately to escape the searing light of my lamp.

“The collector!” Eric demanded. I lifted the collector above my head and aimed it like a telescope at the fleeing enigma, so that Eric could find it in the collectors peeper. The collector spat fire at both ends and jumped up and away. Eric was controlling it now.

After a moment I asked, “Should I come back?”

“Certainly not. Stay there. I can’t bring the collector back to the ship! You’ll have to wait and carry it back with you.

The pool-shadow slid over the edge of the hill. The flame of the collector’s rocket went after it, flying high, growing smaller. It dipped below the ridge. A moment later I heard Eric mutter, “Got it.” The bright flame reappeared, rising fast, then curved toward me.

When the thing was hovering near me on two lateral rockets I picked it up by the tail and carried it home.

“No, no trouble,” said Eric. “I just used the scoop to nip a piece out of his flank, if, so I may speak. I got about ten cubic centimeters of strange flesh.”

“Good,” said I. Carrying the collector carefully in one hand, I went up the landing leg to the airlock. Eric let me in.

I peeled off my frosting suit in the blessed artificial light of ship’s day.

“Okay,” said Eric. “Take it up to the lab. And don’t touch it.”

Eric can be a hell of an annoying character. "I’ve got a brain,” I snarled, “even if you can’t see it.” So can I.

There was a ringing silence while we each tried to dream up an apology. Eric got there first. “Sorry,” he said.

“Me too.” I hauled the collector off to the lab on a cart.

He guided me when I got there. “Put the whole package in that opening. Jaws first. No, don’t close it yet. Turn the thing until these lines match the lines on the collector. Okay. Push it in a little. Now close the door. Okay, Howie, I’ll take it from there …” There were chugging sounds from behind the little door. “Have to wait till the lab’s cool enough. Go get some coffee,” said Eric.

&n

bsp; “I’d better check your maintenance.”

“Okay, good. Go oil my prosthetic aids.”

'Prosthetic aids'—that was a hot one. I’d thought it up myself. I pushed the coffee button so it would be ready when I was through, then opened the big door in the forward wall of the cabin. Eric looked much like an electrical network, except for the gray mass at the top which was his brain. In all directions from his spinal cord and brain, connected at the walls of the intricately shaped glass-and-soft-plastic vessel which housed him, Eric’s nerves reached out to master the ship. The instruments which mastered Eric—but he was sensitive about having it put that way—were banked along both sides of the closet. The blood pump pumped rhythmically, seventy beats a minute.

“How do I look?” Eric asked.

“Beautiful. Are you looking for flattery?”

“Jackass! Am I still alive?”

“The instruments think so. But I’d better lower your fluid temperature a fraction.” I did. Ever since we’d landed I’d had a tendency to keep temperatures too high. “Everything else looks okay. Except your food tank is getting low.”

“Well, it’ll last the trip.”

“Yeah. ‘Scuse me. Eric, coffees ready.” I went and got it. The only thing I really worry about is his “liver.” It’s too complicated. It could break down too easily. If it stopped making blood sugar Eric would be dead.

If Eric dies I die, because Eric is the ship. If I die Eric dies, insane, because he can’t sleep unless I set his prosthetic aids.

I was finishing my coffee when Eric yelled. “Hey!”

“What’s wrong?” I was ready to run in any direction.

“It’s only helium!”

He was astonished and indignant. I relaxed.

The Integral Trees - Omnibus

The Integral Trees - Omnibus A World Out of Time

A World Out of Time Crashlander

Crashlander The World of Ptavvs

The World of Ptavvs Ringworld

Ringworld Juggler of Worlds

Juggler of Worlds The Ringworld Throne

The Ringworld Throne The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic

The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic A Gift From Earth

A Gift From Earth Escape From Hell

Escape From Hell Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII Rainbow Mars

Rainbow Mars Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I Destroyer of Worlds

Destroyer of Worlds Man-Kzin Wars XIV

Man-Kzin Wars XIV Treasure Planet

Treasure Planet N-Space

N-Space Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition

Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition The Ringworld Engineers

The Ringworld Engineers Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII The Magic May Return

The Magic May Return Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven

Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven The Magic Goes Away

The Magic Goes Away Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI Man-Kzin Wars III

Man-Kzin Wars III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI Inferno

Inferno 01-Human Space

01-Human Space Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton

The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton Ringworld's Children

Ringworld's Children Man-Kzin Wars XII

Man-Kzin Wars XII Scatterbrain

Scatterbrain Man-Kzin Wars 9

Man-Kzin Wars 9 Man-Kzin Wars XIII

Man-Kzin Wars XIII Flatlander

Flatlander Man-Kzin Wars V

Man-Kzin Wars V Destiny's Forge

Destiny's Forge Scatterbrain (2003) SSC

Scatterbrain (2003) SSC The Time of the Warlock

The Time of the Warlock Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II

Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9)

Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9) Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8)

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8) Treasure Planet - eARC

Treasure Planet - eARC The Draco Tavern

The Draco Tavern Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti The Fourth Profession

The Fourth Profession Betrayer of Worlds

Betrayer of Worlds Convergent Series

Convergent Series Starborn and Godsons

Starborn and Godsons Protector

Protector Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4)

Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4) The Legacy of Heorot

The Legacy of Heorot 03-Flatlander

03-Flatlander Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII Destiny's Road

Destiny's Road Fate of Worlds

Fate of Worlds Beowulf's Children

Beowulf's Children 04-Protector

04-Protector The Flight of the Horse

The Flight of the Horse Man-Kzin Wars IV

Man-Kzin Wars IV The Moon Maze Game dp-4

The Moon Maze Game dp-4 The California Voodoo Game dp-3

The California Voodoo Game dp-3 07-Beowulf Shaeffer

07-Beowulf Shaeffer Ringworld's Children r-4

Ringworld's Children r-4 The Man-Kzin Wars 05

The Man-Kzin Wars 05 The Man-Kzin Wars 12

The Man-Kzin Wars 12 Lucifer's Hammer

Lucifer's Hammer The Seascape Tattoo

The Seascape Tattoo The Moon Maze Game

The Moon Maze Game Man-Kzin Wars IX

Man-Kzin Wars IX All The Myriad Ways

All The Myriad Ways More Magic

More Magic 02-World of Ptavvs

02-World of Ptavvs ARM

ARM The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld)

The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld) Burning Tower

Burning Tower The Man-Kzin Wars 06

The Man-Kzin Wars 06 The Man-Kzin Wars 03

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC

Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC The Hole Man

The Hole Man The Warriors mw-1

The Warriors mw-1 The Houses of the Kzinti

The Houses of the Kzinti The Man-Kzin Wars 07

The Man-Kzin Wars 07 The Man-Kzin Wars 02

The Man-Kzin Wars 02 The Burning City

The Burning City At the Core

At the Core The Trellis

The Trellis The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1 The Man-Kzin Wars 04

The Man-Kzin Wars 04 The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names

The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names Dream Park

Dream Park How the Heroes Die

How the Heroes Die Oath of Fealty

Oath of Fealty The Smoke Ring t-2

The Smoke Ring t-2 06-Known Space

06-Known Space Destiny's Road h-3

Destiny's Road h-3 Flash crowd

Flash crowd The Man-Kzin Wars 11

The Man-Kzin Wars 11 The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014

The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014 The Ringworld Throne r-3

The Ringworld Throne r-3 A Kind of Murder

A Kind of Murder The Barsoom Project dp-2

The Barsoom Project dp-2 Building Harlequin’s Moon

Building Harlequin’s Moon The Gripping Hand

The Gripping Hand The Leagacy of Heorot

The Leagacy of Heorot Red Tide

Red Tide Choosing Names mw-8

Choosing Names mw-8 Inconstant Moon

Inconstant Moon The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War

The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld

Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld Ringworld r-1

Ringworld r-1 05-A Gift From Earth

05-A Gift From Earth The Integral Trees t-1

The Integral Trees t-1 Footfall

Footfall The Mote In God's Eye

The Mote In God's Eye Achilles choice

Achilles choice The Man-Kzin Wars 01

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 Procrustes

Procrustes The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3 The Goliath Stone

The Goliath Stone The Man-Kzin Wars 09

The Man-Kzin Wars 09