- Home

- Larry Niven

Crashlander Page 13

Crashlander Read online

Page 13

“Which would take it here in five hours,” said Emil. “Total of eleven. A one-gee ship would—”

“Would take too long. Lloobee would go crazy. They must know something about Kdatlyno. In fact, I’ll bet they’re lying about not having Kdatlyno food.”

“Maybe. Okay, assume they’re at least as fast as the Argos. That gives us five hours to play in. Hmmm…?”

“Nineteen ships.” On the timetable they were listed according to class. I crossed out fifteen that didn’t have hyperdrive, crossed out the Argos itself to leave three. Crossed out the Pregnant Banana because it was a cargo job, flown by computer, ten gee with no internal compensating fields. Crossed out the Golden Voyage, a passenger ship smaller than the Argos, with a one-gee drive.

“That’s nice,” said Emil. “Drunkard’s Walk. Say! Remember the hunting party I told you about, with their own yacht?”

“Yah. I know that name.”

“Well, that’s the yacht. Drunkard’s Walk. What did you say?”

“The owner of the yacht. Larchmont Bellamy. I met him once, at Elephant’s house.”

“Go on.”

By then it was too late to bite my tongue, though I didn’t know it yet. “Not much to tell. Elephant’s a friend of mine, a flatlander. He’s got friends all over known space. I walked in at lush hour one afternoon, and Bellamy was there, with a woman named…here she is, Tanya Wilson. She’s in the same hunting party. She’s Bellamy’s age.”

“What’s Bellamy like?”

“He’s three hundred years old, no kidding. He was wearing a checkerboard skin-dye job and a shocking-pink Belter crest. He talked well. Old jokes, but he told them well, and he had some new ones, too.”

“Would he kidnap a Kdatlyno?”

I had to think about that. “He might. He’s no xenophobe; aliens don’t make him nervous, but he doesn’t like them. I remember him telling us that we ought to wipe out the kzinti for good and all. He doesn’t need money, though.”

“Would he do it for kicks?”

Bellamy. Pink bushy eyebrows over deep eyes. A mimic’s voice, a deadpan way of telling a story, deadpan delivery of a punch line. I’d wondered at the time if that was a put-on. In three hundred years you hear the same joke so many times, tell the same story so many ways, change your politics again and again to match a changing universe…Was he deadpan because he didn’t care anymore? How much boredom can you meet in three hundred years?

How many times can you change your morals without losing them all? Bellamy was born before a certain Jinxian biological laboratory produced boosterspice. He reached maturity when the organ banks were the only key to long life, when a criminal’s life wasn’t worth a paper star. He was at draft age when the kzinti were the only known extrasolar civilization and a fearful alien threat. Now civilization included human and nine known alien life-forms, and criminal rehabilitation accounted for half of all published work in biochemistry and psychotherapy.

What would Bellamy’s morals say about Lloobee? If he wouldn’t kidnap a Kdatlyno, would he “steal” one?

“You make your own guess there. I don’t know Bellamy that well.”

“Well, it’s worth checking.” Jilson bent over the timetables. “Mist Demons, he landed a third of the way around the planet! Oh, well. Let’s go rent a car.”

“Hah?”

“We’ll need a car.” He saw he’d left me behind. “To get to their camp. To find out if they rescued Lloobee. You know, the Kdatlyno touch sculptor who—”

“I get the picture. Good-bye and good luck. If they ask who sent you, for Finagle’s sake don’t mention me.”

“That won’t work,” Emil said firmly. “Bellamy won’t talk to me. He doesn’t know me.”

“Apparently I didn’t make it clear. I’ll try again. If we knew who the kidnappers were, which we don’t, we still couldn’t charge in with lasers blazing.”

But he was shaking his head, left, right, left, right. “It’s different now. These men have reputations to protect, don’t they? What would happen to those reputations if all human space knew they’d kidnapped a Kdatlyno?”

“You’re not thinking. Even if everyone on Gummidgy knew the truth, the pirates would simply change the contract. A secrecy clause enforced by monetary penalty.”

Emil slapped the table, and the walls echoed. “Are we just going to sit here while they rob us? You’re a hell of a man to wear a hero’s name!”

“Look, you’re taking this too personally—huh?”

“A hero’s name! Beowulf! He must be turning over in his barrow about now.”

“Who’s Beowulf?”

Emil stood up, putting us eye to eye, so that I could see his utter disgust. “Beowulf was the first epic hero in English literature. He killed monsters bare-handed, and he did it to help people who didn’t even belong to his own country. And you—” He turned away. “I’m going after Bellamy.”

I sat there for what seemed a long time. Any time seems long, when you need to make a decision but can’t. It probably wasn’t more than a minute.

But Emil wasn’t in sight when I ran outside.

I shouted at the man who’d loaned us the timetables. “Hey! Where do you go to rent a car?”

“Public rentals. Dial fourteen in the transfer booth, then walk a block east.”

So the base did have transfer booths. I found one, paid my coin, and dialed.

Getting to public rentals gave me my first chance to look at the base. There wasn’t much to see. Buildings, half of them semipermanent; the base was only four years old. Apartment buildings, laboratories, a nursery school. Overhead, the actinic pinpoint of CY Aquarii hit the weather dome and was diffused into a wide, soft white glow. There were few people about, and all of them were tanned the same shade of black for protection against the savage, invisible ultraviolet outside. Most of them had goggles hung around their necks.

That much I saw while running a block at top speed.

He was getting into a car when I came panting up. He said, “Change your mind?”

“No, but…hoo!…you’re going to change yours. Whew! The mood you’re in, you’ll fly straight into…Bellamy’s camp and…tell him he’s a lousy pirate. Hyooph! Then if you’re wrong, he’ll…punch you in the nose…and if you’re right, he’ll either…laugh at you or have you…killed.”

Emil climbed into the car. “If you’re going to argue, get in and argue there.”

I got in. I had some of my breath back. “Will you get it through your thick head? You’ve got your life to lose and nothing to gain. I told you why.”

“I’ve got to try, don’t I? Fasten your crash web.”

I fastened my crash web. Its strands were thin as coarse thread and not much stronger, but they had saved lives. Any sharp pull on the crash web would activate the crash field, which would enfold the pilot and protect him from impact.

“If you’ve still got to look for the kidnappers,” I said, “why not do it here? There’s a good chance Lloobee’s somewhere on the base.”

“Nuts,” said Emil. He turned on the lift units, and we took off. “Bellamy’s yacht is the only ship that fits.”

“There’s another ship that fits. The Argos.”

“Put your goggles on. We’re about to go through the weather dome. What about the Argos?”

“Think it through. There had to be someone aboard in the first place to plant the gas bomb that knocked us out. Why shouldn’t that same person have hidden Lloobee somewhere, gagged or unconscious, until the Argos could land?”

“Finagle’s gonads! He could still be on the Argos! No, he couldn’t; they searched the Argos.” Emil glared at nothing. At that moment we went through the weather dome. CY Aquarii, which had been a soft white patch, became for an instant a tiny bright point of agony. Then a spot on each lens of my goggles turned black and covered the sun.

“We’ll have to check it out later,” said Emil. “But we can call city hall now and tell them one of the kidnappers was on the

Argos.”

But we couldn’t. Where the car radio should have been was a square hole.

Emil smote his forehead. With his Jinxian strength it’s a wonder he survived. “I forgot. Car radios won’t work on Gummidgy. You have to use a ship’s com laser and bounce the beam off one of the orbital stations.”

“Do we have a com laser?”

“Do you see one? Maybe in ten years someone’ll think of putting com lasers in cars. Well, we’ll have to do it later.”

“That’s silly. Let’s do it now.”

“First we check on Bellamy.”

“I’m not going.”

Emil just grinned.

He was right. It had been a futile comment. I had three choices:

Fighting a Jinxian.

Getting out and walking home. But we must have gone a mile up already, and the base was far behind.

Visiting Bellamy, who was an old friend, and looking around unobtrusively while we were there. Actually, it would have been rude not to go. Actually, it would have been silly not to at least drop by and say hello while we were on the same planet.

Actually, I rationalize a lot.

“Do one thing for me,” I said. “Let me do all the talking. You can be the strong, silent type who smiles a lot.”

“Okay. What are you going to tell him?”

“The truth. Not the whole truth, but some of it.”

The four-hour trip passed quickly. We found cards and a score pad in a glove compartment. The car blasted quietly and smoothly through a Mach four wall of air, rising once to clear a magnificent range of young mountains.

“Can you fly a car?”

I looked up from my cards. “Of course.” Most people can. Every world has its wilderness areas, and it’s not worthwhile to spread transfer booths all through a forest, especially one that doesn’t see twenty tourists in a year. When you’re tired of civilization, the only way to travel is to transfer to the edge of a planetary park and then rent a car.

“That’s good,” said Emil, “in case I get put out of action.”

“Now it’s your turn to cheer me up.”

Emil cocked his head at me. “If it’s any help, I think I know how Bellamy’s group found the Argos.”

“Go on.”

“It was the starseed. A lot of people must have known about it, including Margo. Maybe she told someone that she was stopping the ship so the passengers could get a look.”

“Not much help. She had a lot of space to stop in.”

“Did she? Think about it. First, Bellamy’d have no trouble at all figuring when she’d reach the Gummidgy system.”

“Right.” There’s only one speed in hyperdrive.

“That means Margo would have to stop on a certain spherical surface to catch the light image of the starseed setting sail. Furthermore, in order to watch it happen in an hour, she had to be right in front of the starseed. That pinpoints her exactly.”

“There’d be a margin of error.”

Emil shrugged. “Half a light-hour on a side. All Bellamy had to do was wait in the right place. He had an hour to maneuver.”

“Bravo,” I said. There were things I didn’t want him to know yet. “He could have done it that way, all right. I’d like to mention just one thing.”

“Go ahead.”

“You keep saying ‘Bellamy did this’ and ‘Bellamy did that.’ We don’t know he’s guilty yet, and I’ll thank you to remember it. Remember that he’s a friend of a friend and don’t start treating him like a criminal until you know he is one.”

“All right,” Emil said, but he didn’t like it. He knew Bellamy was a kidnapper. He was going to get us both killed if he didn’t watch his mouth.

At the last minute I got a break. It was only a bit of misinterpretation on Emil’s part, but one does not refuse a gift from the gods.

We’d crossed six or seven hundred kilometers of veldt: blue-green grass with herds grazing at wide intervals. The herds left a clear path, for the grass (or whatever, we hadn’t seen it close up) changed color when cropped. Now we were coming up on a forest, but not the gloomy green type of forest native to human space. It was a riot of color: patches of scarlet, green, magenta, yellow. The yellow patches were polka-dotted with deep purple.

Just this side of the forest was the hunting camp. Like a nudist at a tailors’ convention, it leapt to the eye, flagrantly alien against the blue-green veldt. A bulbous plastic camp tent the size of a mansion dominated the scene, creases marring its translucent surface to show where it was partitioned into rooms. A diminutive figure sat outside the door, its head turning to follow our sonic boom. The yacht was some distance away.

The yacht was a gaily decorated playboy’s space boat with a brilliant orange paint job and garish markings in colors that clashed. Some of the markings seemed to mean something. Bellamy, one year ago, hadn’t struck me as the type to own such a boat. Yet there it stood, on three wide landing legs with paddle-shaped feet, its sharp nose pointed up at us.

It looked ridiculous. The hull was too thick and the legs were too wide, so that the big businesslike attitude jets in the nose became a comedian’s nostrils. On a slender needle with razor-sharp swept-back airfoils that paint job might have passed. But it made the compact, finless Drunkard’s Walk look like a clown.

The camp swept under us while we were still moving at Mach two. Emil tilted the car into a wide curve, slowing and dropping. As we turned toward the camp for the second time, he said, “Bellamy’s taking precious little pains to hide himself. Oh, oh.”

“What?”

“The yacht. It’s not big enough. The ship Captain Tellefsen described was twice that size.”

A gift from the gods. “I hadn’t noticed,” I said. “You’re right. Well, that lets Bellamy out.”

“Go ahead. Tell me I’m an idiot.”

“No need. Why should I gloat over one stupid mistake? I’d have had to make the trip anyway, sometime.”

Emil sighed. “I suppose that means you’ll have to see Bellamy before we go back.”

“Finagle’s sake, Emil! We’re here, aren’t we? Oh, one thing. Let’s not tell Bellamy why we came. He might be offended.”

“And he might decide I’m a dolt. Correctly. Don’t worry, I won’t tell him.”

The “grass” covering the veldt turned out to be knee-high ferns, dry and brittle enough to crackle under our socks. Dark blue-green near the tips of the plants gave way to lighter coloring on the stalks. Small wonder the herbivores had left a trail. Small wonder if we’d seen carnivores treading that easy path.

The goggled figure in front of the camp tent was cleaning a mercy rifle. By the time we were out of the car, he had closed it up and loaded it with inch-long slivers of anesthetic chemical. I’d seen such guns before. The slivers could be fired individually or in one-second bursts of twenty, and they dissolved instantly in anything that resembled blood. One type of sliver would usually fit all the life-forms on a given world.

The man didn’t bother to get up as we approached. Nor did he put down the gun. “Hi,” he said cheerfully. “What can I do for you?”

“We’d like—”

“Beowulf Shaeffer?”

“Yah. Larch Bellamy?”

Now he got up. “Can’t recognize anybody on this crazy world. Goggles covering half your face, everybody the same color—you have to go stark naked to be recognized, and then only the women know you. Whatinhell are you doing on Gummidgy, Bey?”

“I’ll tell you later. Larch, this is Emil Horne. Emil, meet Larchmont Bellamy.”

“Pleasure,” said Bellamy, grinning as if indeed it were. Then his grin tried to break into laughter, and he smothered it. “Let’s go inside and swallow something wet.”

“What was funny?”

“Don’t be offended, Mr. Horne. You and Bey do make an odd pair. I was thinking that the two of you are like a medium-sized beach ball standing next to a baseball bat. How did you meet?”

“On the ship,” sa

id Emil.

The camp tent had a collapsible revolving door to hold the pressure. Inside, the tent was almost luxurious, though it was all foldaway stuff. Chairs and sofas were soft, cushiony fabric surfaces, holding their shape through insulated static charges. Tables were memory plastic. Probably they compressed into small cubes for storage aboard ship. Light came from glow strips in the fabric of the pressurized tent. The bar was a floating portable. It came to meet us at the door, took our orders, and passed out drinks.

“All right,” Bellamy said, sprawling in an armchair. When he relaxed, he relaxed totally, like a cat. Or a tiger. “Bey, how did you come to Gummidgy? And where’s Sharrol?”

“She can’t travel in space.”

“Oh? I didn’t know. That can happen to anyone.” But his eyes questioned.

“She wanted children. Did you know that? She’s always wanted children.”

He took in my red eyes and white hair. “I…see. So you broke up.”

“For the time being.”

His eyes questioned.

That’s not emphatic enough. There was something about Bellamy…He had a lean body and a lean face, with a straight, sharp-edged nose and prominent cheekbones, all setting off the dark eyes in their deep pits beneath black shaggy brows.

But there was more to it than eyes. You can’t tell a man’s age by looking at his photo, not if he takes boosterspice. But you can tell, to some extent, by watching him in motion. Older men know where they’re going before they start to move. They don’t dither, they don’t waste energy, they don’t trip over their feet, and they don’t bump into things.

Bellamy was old. There was a power in him, and his eyes questioned.

I shrugged. “We used the best answer we had, Larch. He was a friend of ours, and his name was Carlos Wu. You’ve heard of him?”

“Mathematician, isn’t he?”

“Yah. Also playwright and composer. The Fertility Board gave him an unlimited breeding license when he was eighteen.”

The Integral Trees - Omnibus

The Integral Trees - Omnibus A World Out of Time

A World Out of Time Crashlander

Crashlander The World of Ptavvs

The World of Ptavvs Ringworld

Ringworld Juggler of Worlds

Juggler of Worlds The Ringworld Throne

The Ringworld Throne The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic

The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic A Gift From Earth

A Gift From Earth Escape From Hell

Escape From Hell Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII Rainbow Mars

Rainbow Mars Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I Destroyer of Worlds

Destroyer of Worlds Man-Kzin Wars XIV

Man-Kzin Wars XIV Treasure Planet

Treasure Planet N-Space

N-Space Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition

Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition The Ringworld Engineers

The Ringworld Engineers Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII The Magic May Return

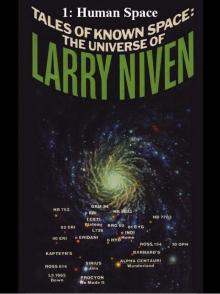

The Magic May Return Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven

Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven The Magic Goes Away

The Magic Goes Away Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI Man-Kzin Wars III

Man-Kzin Wars III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI Inferno

Inferno 01-Human Space

01-Human Space Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton

The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton Ringworld's Children

Ringworld's Children Man-Kzin Wars XII

Man-Kzin Wars XII Scatterbrain

Scatterbrain Man-Kzin Wars 9

Man-Kzin Wars 9 Man-Kzin Wars XIII

Man-Kzin Wars XIII Flatlander

Flatlander Man-Kzin Wars V

Man-Kzin Wars V Destiny's Forge

Destiny's Forge Scatterbrain (2003) SSC

Scatterbrain (2003) SSC The Time of the Warlock

The Time of the Warlock Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II

Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9)

Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9) Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8)

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8) Treasure Planet - eARC

Treasure Planet - eARC The Draco Tavern

The Draco Tavern Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti The Fourth Profession

The Fourth Profession Betrayer of Worlds

Betrayer of Worlds Convergent Series

Convergent Series Starborn and Godsons

Starborn and Godsons Protector

Protector Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4)

Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4) The Legacy of Heorot

The Legacy of Heorot 03-Flatlander

03-Flatlander Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII Destiny's Road

Destiny's Road Fate of Worlds

Fate of Worlds Beowulf's Children

Beowulf's Children 04-Protector

04-Protector The Flight of the Horse

The Flight of the Horse Man-Kzin Wars IV

Man-Kzin Wars IV The Moon Maze Game dp-4

The Moon Maze Game dp-4 The California Voodoo Game dp-3

The California Voodoo Game dp-3 07-Beowulf Shaeffer

07-Beowulf Shaeffer Ringworld's Children r-4

Ringworld's Children r-4 The Man-Kzin Wars 05

The Man-Kzin Wars 05 The Man-Kzin Wars 12

The Man-Kzin Wars 12 Lucifer's Hammer

Lucifer's Hammer The Seascape Tattoo

The Seascape Tattoo The Moon Maze Game

The Moon Maze Game Man-Kzin Wars IX

Man-Kzin Wars IX All The Myriad Ways

All The Myriad Ways More Magic

More Magic 02-World of Ptavvs

02-World of Ptavvs ARM

ARM The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld)

The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld) Burning Tower

Burning Tower The Man-Kzin Wars 06

The Man-Kzin Wars 06 The Man-Kzin Wars 03

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC

Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC The Hole Man

The Hole Man The Warriors mw-1

The Warriors mw-1 The Houses of the Kzinti

The Houses of the Kzinti The Man-Kzin Wars 07

The Man-Kzin Wars 07 The Man-Kzin Wars 02

The Man-Kzin Wars 02 The Burning City

The Burning City At the Core

At the Core The Trellis

The Trellis The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1 The Man-Kzin Wars 04

The Man-Kzin Wars 04 The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names

The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names Dream Park

Dream Park How the Heroes Die

How the Heroes Die Oath of Fealty

Oath of Fealty The Smoke Ring t-2

The Smoke Ring t-2 06-Known Space

06-Known Space Destiny's Road h-3

Destiny's Road h-3 Flash crowd

Flash crowd The Man-Kzin Wars 11

The Man-Kzin Wars 11 The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014

The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014 The Ringworld Throne r-3

The Ringworld Throne r-3 A Kind of Murder

A Kind of Murder The Barsoom Project dp-2

The Barsoom Project dp-2 Building Harlequin’s Moon

Building Harlequin’s Moon The Gripping Hand

The Gripping Hand The Leagacy of Heorot

The Leagacy of Heorot Red Tide

Red Tide Choosing Names mw-8

Choosing Names mw-8 Inconstant Moon

Inconstant Moon The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War

The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld

Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld Ringworld r-1

Ringworld r-1 05-A Gift From Earth

05-A Gift From Earth The Integral Trees t-1

The Integral Trees t-1 Footfall

Footfall The Mote In God's Eye

The Mote In God's Eye Achilles choice

Achilles choice The Man-Kzin Wars 01

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 Procrustes

Procrustes The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3 The Goliath Stone

The Goliath Stone The Man-Kzin Wars 09

The Man-Kzin Wars 09