- Home

- Larry Niven

Crashlander Page 18

Crashlander Read online

Page 18

The drive ran sure and smooth up to a maximum at ten gravities: not a lot for a ship designed to haul massive cargo. The cabin gravity held without putting out more than a fraction of its power. When Jinx and Primary were invisible against the stars, when Sirius was so distant that I could look directly at it, I turned to the hidden control panel Ausfaller had unlocked for me. Ausfaller woke up, found me doing that, and began showing me which did what.

He had a big X-ray laser and some smaller laser cannon set for different frequencies. He had four self-guided fusion bombs. He had a telescope so good that the ostensible ship’s telescope was only a finder for it. He had deep radar.

And none of it showed beyond the discolored hull.

Ausfaller was armed for Bandersnatchi. I felt mixed emotions. It seemed we could fight anything and run from it, too. But what kind of enemy was he expecting?

An through those four weeks in hyperdrive, while we drove through the Blind Spot at three days to the light-year, the topic of the ship eaters reared its disturbing head.

Oh, we spoke of other things: of music and art and of the latest techniques in animation, the computer programs that let you make your own holo flicks almost for lunch money. We told stories. I told Carlos why the Kdatlyno Lloobee had made busts of me and Emil Home. I spoke of the only time the Pierson’s Puppeteers had ever paid off the guarantee on a General Products hull, after the supposedly indestructible hull had been destroyed by antimatter. Ausfaller had some good ones…a lot more stories than he was allowed to tell, I gathered, from the way he had to search his memory every time.

But we kept coming back to the ship eaters.

“It boils down to three possibilities,” I decided. “Kzinti, puppeteers, and humans.”

Carlos guffawed. “Puppeteers? Puppeteers wouldn’t have the guts!”

“I threw them in because they might have some interest in manipulating the interstellar stock market. Look, our hypothetical pirates have set up an embargo, cutting Sol System off from the outside world. The puppeteers have the capital to take advantage of what that does to the market. And they need money. For their migration.”

“The puppeteers are philosophical cowards.”

“That’s right. They wouldn’t risk robbing the ships or coming anywhere near them. Suppose they can make them disappear from a distance?”

Carlos wasn’t laughing now. “That’s easier than dropping them out of hyperspace to rob them. It wouldn’t take more than a great big gravity generator…and we’ve never known the limits of puppeteer technology.”

Ausfaller asked, “You think this is possible?”

“Just barely. The same goes for the kzinti. The kzinti are ferocious enough. Trouble is, if we ever learned they were preying on our ships, we’d raise pluperfect hell. The kzinti know that, and they know we can beat them. Took them long enough, but they learned.”

“So you think it’s humans,” said Carlos.

“Yah. If it’s pirates.”

The piracy theory still looked shaky. Spectrum telescopes had not even found concentrations of ship’s metals in the space where they have vanished. Would pirates steal the whole ship? If the hyperdrive motor was still intact after the attack, the rifled ship could be launched into infinity, but could pirates count on that happening eight times out of eight?

And none of the missing ships had called for help via hyperwave.

I’d never believed pirates. Space pirates have existed, but they died without successors. Intercepting a spacecraft was too difficult. They couldn’t make it pay.

Ships fly themselves in hyperdrive. All a pilot need do is watch for green radial lines in the mass-sensor. But he has to do that frequently, because the mass sensor is a psionic device; it must be watched by a mind, not another machine.

As the narrow green line that marked Sol grew longer, I became abnormally conscious of the debris around Sol System. I spent the last twelve hours of the flight at the controls, chain-smoking with my feet. I should add that I do that normally when I want both hands free, but now I did it to annoy Ausfaller. I’d seen the way his eyes bugged the first time he saw me take a drag from a cigarette between my toes. Flatlanders are less than limber.

Carlos and Ausfaller shared the control room with me as we penetrated Sol’s cometary halo. They were relieved to be nearing the end of a long trip. I was nervous. “Carlos, just how large a mass would it take to make us disappear?”

“Planet size, Mars and up. Beyond that it depends on how close you get and how dense it is. If it’s dense enough, it can be less massive and still flip you out of the universe. But you’d see it in the mass sensor.”

“Only for an instant…and not then, if it’s turned off. What if someone turned on a giant gravity generator as we went past?”

“For what? They couldn’t rob the ship. Where’s their profit?”

“Stocks.”

But Ausfaller was shaking his head. “The expense of such an operation would be enormous. No group of pirates would have enough additional capital on hand to make it worthwhile. Of the puppeteers I might believe it.”

Hell, he was right. No human that wealthy would need to turn pirate.

The long green line marking Sol was almost touching the surface of the mass sensor. I said, “Breakout in ten minutes.”

And the ship lurched savagely.

“Strap down!” I yelled, and glanced at the hyperdrive monitors. The motor was drawing no power, and the rest of the dials were going bananas.

I activated the windows. I’d kept them turned off in hyperspace lest my flatlander passengers go mad watching the Blind Spot. The screens came on, and I saw stars. We were in normal space.

“Futz! They got us anyway.” Carlos sounded neither frightened nor angry, but awed.

As I raised the hidden panel Ausfaller cried, “Wait!” I ignored him. I threw the red switch, and Hobo Kelly lurched again as her belly blew off.

Ausfaller began cursing in some dead flatlander language.

Now two-thirds of Hobo Kelly receded, slowly turning. What was left must show as what she was: a No. 2 General Products hull, puppeteer-built, a slender transparent spear three hundred feet long and twenty feet wide, with instruments of war clustered along what was now her belly. Screens that had been blank came to life. And I lit the main drive and ran it up to full power.

Ausfaller spoke in rage and venom. “Shaeffer, you idiot, you coward! We run without knowing what we run from. Now they know exactly what we are. What chance that they will follow us now? This ship was built for a specific purpose, and you have ruined it!”

“I’ve freed your special instruments,” I pointed out. “Why don’t you see what you can find?” Meanwhile I could get us the futz out of here.

Ausfaller became very busy. I watched what he was getting on screens at my side of the control panel. Was anything chasing us? They’d find us hard to catch and harder to digest. They could hardly have been expecting a General Products hull. Since the puppeteers stopped making them, the price of used GP hulls has gone out of sight.

There were ships out there. Ausfaller got a close-up of them: three space tugs of the Belter type, shaped like thick saucers, equipped with oversized drives and powerful electromagnetic generators. Belters use them to tug nickel-iron asteroids to where somebody wants the ore. With those heavy drives they could probably catch us, but would they have adequate cabin gravity?

They weren’t trying. They seemed to be neither following nor fleeing. And they looked harmless enough.

But Ausfaller was doing a job on them with his other instruments. I approved. Hobo Kelly had looked peaceful enough a moment ago. Now her belly bristled with weaponry. The tugs could be equally deceptive.

From behind me Carlos asked, “Bey? What happened?”

“How the futz would I know?”

“What do the instruments show?”

He must mean the hyperdrive complex. A couple of the indicators had gone wild; five more were dead. I said so. “A

nd the drive’s drawing no power at all. I’ve never heard of anything like this. Carlos, it’s still theoretically impossible.”

“I’m…not so sure of that. I want to look at the drive.”

“The access tubes don’t have cabin gravity.”

Ausfaller had abandoned the receding tugs. He’d found what looked to be a large comet, a ball of frozen gases a good distance to the side. I watched as he ran the deep radar over it. No fleet of robber ships lurked behind it.

I asked, “Did you deep-radar the tugs?”

“Of course. We can examine the tapes in detail later. I saw nothing. And nothing has attacked us since we left hyperspace.”

I’d been driving us in a random direction. Now I turned us toward Sol, the brightest star in the heavens. Those lost ten minutes in hyperspace would add about three days to our voyage.

“If there was an enemy, you frightened him away. Shaeffer, this mission and this ship have cost my department an enormous sum, and we have learned nothing at all.”

“Not quite nothing,” said Carlos. “I still want to see the hyperdrive motor. Bey, would you run us down to one gee?”

“Yah. But…miracles make me nervous, Carlos.”

“Join the club.”

We crawled along an access tube just a little bigger than a big man’s shoulders, between the hyperdrive motor housing and the surrounding fuel tankage. Carlos reached an inspection window. He looked in. He started to laugh.

I inquired as to what was so futzy funny.

Still chortling, Carlos moved on. I crawled after him and looked in.

There was no hyperdrive motor in the hyperdrive motor housing.

I went in through a repair hatch and stood in the cylindrical housing, looking about me. Nothing. Not even an exit hole. The superconducting cables and the mounts for the motor had been sheared so cleanly that the cut ends looked like little mirrors.

Ausfaller insisted on seeing for himself. Carlos and I waited in the control room. For a while Carlos kept bursting into fits of giggles. Then he got a dreamy, faraway look that was even more annoying.

I wondered what was going on in his head and reached the uncomfortable conclusion that I could never know. Some years ago I took IQ tests, hoping to get a parenthood license that way. I am not a genius.

I knew only that Carlos had thought of something I hadn’t, and he wasn’t telling, and I was too proud to ask.

Ausfaller had no pride. He came back looking like he’d seen a ghost. “Gone! Where could it go? How could it happen?”

“That I can answer,” Carlos said happily. “It takes an extremely high gravity gradient. The motor hit that, wrapped space around itself, and took off at some higher level of hyperdrive, one we can’t reach. By now it could be well on its way to the edge of the universe.”

I said, “You’re sure, huh? An hour ago there wasn’t a theory to cover any of this.”

“Well, I’m sure our motor’s gone. Beyond that it gets a little hazy. But this is one well-established model of what happens when a ship hits a singularity. At a lower gravity gradient the motor would take the whole ship with it, then strew atoms of the ship along its path till there was nothing left but the hyperdrive field itself.”

“Ugh.”

Now Carlos burned with the love of an idea. “Sigmund, I want to use your hyperwave. I could still be wrong, but there are things we can check.”

“If we are still within the singularity of some mass, the hyperwave will destroy itself.”

“Yah. I think it’s worth the risk.”

We’d dropped out, or been knocked out, ten minutes short of the singularity around Sol. That added up to sixteen light-hours of normal space, plus almost five light-hours from the edge of the singularity inward to Earth. Fortunately, hyperwave is instantaneous, and every civilized system keeps a hyperwave relay station just outside the singularity. Southworth Station would relay our message inward by laser, get the return message the same way, and pass it on to us ten hours later.

We turned on the hyperwave, and nothing exploded.

Ausfaller made his own call first, to Ceres, to get the registry of the tugs we’d spotted. Afterward Carlos called Elephant’s computer setup in New York, using a code number Elephant doesn’t give to many people. “I’ll pay him back later. Maybe with a story to go with it,” he gloated.

I listened as Carlos outlined his needs. He wanted full records on a meteorite that had touched down in Tunguska, Siberia, USSR, Earth, in 1908 A.D. He wanted a reprise on three models of the origin of the universe or lack of same: the big bang, the cyclic universe, and the steady state universe. He wanted data on collapsars. He wanted names, career outlines, and addresses for the best known students of gravitational phenomena in Sol system. He was smiling when he clicked off.

I said, “You got me. I haven’t the remotest idea what you’re after.”

Still smiling, Carlos got up and went to his cabin to catch some sleep.

I turned off the main thrust motor entirely. When we were deep in Sol system, we could decelerate at thirty gravities. Meanwhile we were carrying a hefty velocity picked up on our way out of Sirius system.

Ausfaller stayed in the control room. Maybe his motive was the same as mine. No police ships out here. We could still be attacked.

He spent the time going through his pictures of the three mining tugs. We didn’t talk, but I watched.

The tugs seemed ordinary enough. Telescopic photos showed no suspicious breaks in the hulls, no hatches for guns. In the deep-radar scan they showed like ghosts: we could pick out the massive force-field rings, the hollow, equally massive drive tubes, the lesser densities of fuel tank and life-support system. There were no gaps or shadows that shouldn’t have been there.

By and by Ausfaller said, “Do you know what Hobo Kelly was worth?”

I said I could make a close estimate.

“It was worth my career. I thought to destroy a pirate fleet with Hobo Kelly. But my pilot fled. Fled! What have I now, to show for my expensive Trojan horse?”

I suppressed the obvious answer, along with the plea that my first responsibility was Carlos’s life. Ausfaller wouldn’t buy that. Instead, “Carlos has something. I know him. He knows how it happened.”

“Can you get it out of him?”

“I don’t know.” I could put it to Carlos that we’d be safer if we knew what was out to get us. But Carlos was a flatlander. It would color his attitudes.

“So,” said Ausfaller. “We have only the unavailable knowledge in Carlos’s skull.”

A weapon beyond human technology had knocked me out of hyperspace. I’d run. Of course I’d run. Staying in the neighborhood would have been insane, said I to myself, said I. But, unreasonably, I still felt bad about it.

To Ausfaller I said, “What about the mining tugs? I can’t understand what they’re doing out here. In the Belt they use them to move nickel-iron asteroids to industrial sites.”

“It is the same here. Most of what they find is useless—stony masses or balls of ice—but what little metal there is, is valuable. They must have it for building.”

“For building what? What kind of people would live here? You might as well set up shop in interstellar space!”

“Precisely. There are no tourists, but there are research groups here where space is flat and empty and temperatures are near absolute zero. I know that the Quicksilver Group was established here to study hyperspace phenomena. We do not understand hyperspace, even yet. Remember that we did not invent the hyperdrive; we bought it from an alien race. Then there is a gene-tailoring laboratory trying to develop a kind of tree that will grow on comets.”

“You’re kidding.”

“But they are serious. A photosynthetic plant to use the chemicals present in all comets…it would be very valuable. The whole cometary halo could be seeded with oxygen-producing plants—” Ausfaller stopped abruptly, then, “Never mind. But all these groups need building materials. It is cheaper to build out her

e than to ship everything from Earth or the Belt. The presence of tugs is not suspicious.”

“But there was nothing else around us. Nothing at all.”

Ausfaller nodded.

When Carlos came to join us many hours later, blinking sleep out of his eyes, I asked him, “Carlos, could the tugs have had anything to do with your theory?”

“I don’t see how. I’ve got half an idea, and half an hour from now I could look like a half-wit. The theory I want isn’t even in fashion anymore. Now that we know what the quasars are, everyone seems to like the steady state hypothesis. You know how that works: the tension in completely empty space produces more hydrogen atoms, forever. The universe has no beginning and no end.” He looked stubborn. “But if I’m right, then I know where the ships went to after being robbed. That’s more than anyone else knows.”

Ausfaller jumped on him. “Where are they? Are the passengers alive?”

“I’m sorry, Sigmund. They’re all dead. There won’t even be bodies to bury.”

“What is it? What are we fighting?”

“A gravitational effect. A sharp warping of space. A planet wouldn’t do that, and a battery of cabin gravity generators wouldn’t do it; they couldn’t produce that sharply bounded a field.”

“A collapsar,” Ausfaller suggested.

Carlos grinned at him. “That would do it, but there are other problems. A collapsar can’t even form at less than around five solar masses. You’d think someone would have noticed something that big, this close to Sol.”

“Then what?”

Carlos shook his head. We would wait.

The relay from Southworth Station gave us registration for three space tugs, used and of varying ages, all three purchased two years ago from IntraBelt Mining by the Sixth Congregational Church of Rodney.

“Rodney?”

But Carlos and Ausfaller were both chortling. “Belters do that sometimes,” Carlos told me. “It’s a way of saying it’s nobody’s business who’s buying the ships.”

The Integral Trees - Omnibus

The Integral Trees - Omnibus A World Out of Time

A World Out of Time Crashlander

Crashlander The World of Ptavvs

The World of Ptavvs Ringworld

Ringworld Juggler of Worlds

Juggler of Worlds The Ringworld Throne

The Ringworld Throne The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic

The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic A Gift From Earth

A Gift From Earth Escape From Hell

Escape From Hell Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII Rainbow Mars

Rainbow Mars Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I Destroyer of Worlds

Destroyer of Worlds Man-Kzin Wars XIV

Man-Kzin Wars XIV Treasure Planet

Treasure Planet N-Space

N-Space Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition

Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition The Ringworld Engineers

The Ringworld Engineers Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII The Magic May Return

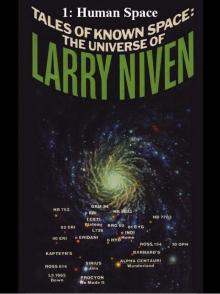

The Magic May Return Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven

Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven The Magic Goes Away

The Magic Goes Away Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI Man-Kzin Wars III

Man-Kzin Wars III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI Inferno

Inferno 01-Human Space

01-Human Space Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton

The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton Ringworld's Children

Ringworld's Children Man-Kzin Wars XII

Man-Kzin Wars XII Scatterbrain

Scatterbrain Man-Kzin Wars 9

Man-Kzin Wars 9 Man-Kzin Wars XIII

Man-Kzin Wars XIII Flatlander

Flatlander Man-Kzin Wars V

Man-Kzin Wars V Destiny's Forge

Destiny's Forge Scatterbrain (2003) SSC

Scatterbrain (2003) SSC The Time of the Warlock

The Time of the Warlock Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II

Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9)

Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9) Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8)

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8) Treasure Planet - eARC

Treasure Planet - eARC The Draco Tavern

The Draco Tavern Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti The Fourth Profession

The Fourth Profession Betrayer of Worlds

Betrayer of Worlds Convergent Series

Convergent Series Starborn and Godsons

Starborn and Godsons Protector

Protector Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4)

Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4) The Legacy of Heorot

The Legacy of Heorot 03-Flatlander

03-Flatlander Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII Destiny's Road

Destiny's Road Fate of Worlds

Fate of Worlds Beowulf's Children

Beowulf's Children 04-Protector

04-Protector The Flight of the Horse

The Flight of the Horse Man-Kzin Wars IV

Man-Kzin Wars IV The Moon Maze Game dp-4

The Moon Maze Game dp-4 The California Voodoo Game dp-3

The California Voodoo Game dp-3 07-Beowulf Shaeffer

07-Beowulf Shaeffer Ringworld's Children r-4

Ringworld's Children r-4 The Man-Kzin Wars 05

The Man-Kzin Wars 05 The Man-Kzin Wars 12

The Man-Kzin Wars 12 Lucifer's Hammer

Lucifer's Hammer The Seascape Tattoo

The Seascape Tattoo The Moon Maze Game

The Moon Maze Game Man-Kzin Wars IX

Man-Kzin Wars IX All The Myriad Ways

All The Myriad Ways More Magic

More Magic 02-World of Ptavvs

02-World of Ptavvs ARM

ARM The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld)

The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld) Burning Tower

Burning Tower The Man-Kzin Wars 06

The Man-Kzin Wars 06 The Man-Kzin Wars 03

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC

Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC The Hole Man

The Hole Man The Warriors mw-1

The Warriors mw-1 The Houses of the Kzinti

The Houses of the Kzinti The Man-Kzin Wars 07

The Man-Kzin Wars 07 The Man-Kzin Wars 02

The Man-Kzin Wars 02 The Burning City

The Burning City At the Core

At the Core The Trellis

The Trellis The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1 The Man-Kzin Wars 04

The Man-Kzin Wars 04 The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names

The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names Dream Park

Dream Park How the Heroes Die

How the Heroes Die Oath of Fealty

Oath of Fealty The Smoke Ring t-2

The Smoke Ring t-2 06-Known Space

06-Known Space Destiny's Road h-3

Destiny's Road h-3 Flash crowd

Flash crowd The Man-Kzin Wars 11

The Man-Kzin Wars 11 The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014

The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014 The Ringworld Throne r-3

The Ringworld Throne r-3 A Kind of Murder

A Kind of Murder The Barsoom Project dp-2

The Barsoom Project dp-2 Building Harlequin’s Moon

Building Harlequin’s Moon The Gripping Hand

The Gripping Hand The Leagacy of Heorot

The Leagacy of Heorot Red Tide

Red Tide Choosing Names mw-8

Choosing Names mw-8 Inconstant Moon

Inconstant Moon The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War

The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld

Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld Ringworld r-1

Ringworld r-1 05-A Gift From Earth

05-A Gift From Earth The Integral Trees t-1

The Integral Trees t-1 Footfall

Footfall The Mote In God's Eye

The Mote In God's Eye Achilles choice

Achilles choice The Man-Kzin Wars 01

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 Procrustes

Procrustes The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3 The Goliath Stone

The Goliath Stone The Man-Kzin Wars 09

The Man-Kzin Wars 09