- Home

- Larry Niven

Oath of Fealty Page 26

Oath of Fealty Read online

Page 26

"I can send for some troops."

Bonner's office was filled with police when Tony Rand came in. LAPD, D.A.'s men, deputy sheriffs, even a marshal from the federal district court, all waiting expectantly, until Colonel Cross and five Todos Santos guards brought in their prisoners.

They were both women. The male prisoner had collapsed from heat exhaustion, and would be taken by ambulance to the prison ward of County Hospital.

Tony Rand stared at the women unashamedly. It was the first time he'd seen them without their protective equipment and masks.

"Something wrong with me, fat boy?" one asked.

"Yes," Tony said. "You want to burn down my city."

"That's the court magician," the other woman said. "He designed this place. The chief technologist."

"So now he's here with the pigs."

"Enough." One of the policemen came forward. "You're under arrest. You have the right to remain silent. You have the right to consult an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney-"

"Of course we gave them their rights earlier on," Colonel Cross announced. He seemed annoyed that anyone would doubt it.

"It never hurts to repeat it," a federal marshal said. "Sounds just like TV, doesn't it, Sherry? Don't worry, officer, we'll go quietly. What are we charged with?"

"Suspicion of homicide," the policeman said.

"0, wow-"

"That's a heavy trip," Sherry said. "We didn't kill anybody. Their pigs killed our friends."

"Your friends were killed during the commission of a felony," the Los Angeles policeman said. "That makes anyone involved in that felony an accomplice to homicide. You should discuss this with your attorney, not with me. Gomez, take them out."

"Yes sir." The uniformed policeman came forward and expertly handcuffed each of the women. Then with two policewomen and half a dozen other police he escorted them out of Bonner's office.

"There's one more," Bonner said. "But I thought you might want to keep them separated. Colonel-"

"Yes, sir," Colonel Cross said. He spoke into a microphone attached to his lapel, and a moment later a guard led Alice into the room.

Despite the police who had left with Sergeant Gomez, there were half a dozen left. Alice blinked as she looked at each face. When her eyes met Tony's, they fell quickly.

The LA officer came forward again. "Alice Strahler, you're under arrest. You have the right to remain silent. You have-"

Alice listened to the entire Miranda warning without comment.

Tony Rand couldn't stand it any longer. "Why?' he asked. "Alice, why?"

She shook her head.

"I trusted you-"

"Yes, sir," Alice said. "So did a lot of people."

"People who got killed!" Tony said. "You - damn you, you made us kill people! You made Pres Sanders into a basket case, and-"

"That's not fair," Alice said. "You know I can't talk about any of that! Not here, with all these police-"

"Pres did," Tony said. "And I still don't understand you. You worked here. You knew what we were building, that people like it here, we don't pollute, we-"

"You don't live like humans, either," Alice Said. "And even if you call this human life, it's not for very many people. Todos Santos is beautiful, Tony, but it uses too many resources to support too few people. The more successful Todos Santos is, the worse it will be for everyone else, don't you understand that? Don't you understand that technology is not the answer, that using technology to fix problems created by technology only puts you in an endless chain? That the more success you have, the more you make people believe that 'Progress' is possible, and Progress just leads to more technology and more waste and more doom-"

"Alice, you wear glasses," Tony said mildly. "You probably use tampons."

"One thing I do understand," Art Bonner said. "You gave us good reason to trust you. We believed you, and you betrayed us. I'm sorry your friends were killed, but I'm not sorry they can charge you with murder."

Murder. Damn, of course, she was in the conspiracy, and that led to murder and- Conspiracy.

Eventually the outsiders left. Tony turned to go. "A moment of your time," Bonner said.

"Yeah?"

"There are a lot of cops wandering around here," Bonner said. "Like a well-smoked beehive. And reporters. And everyone else, all looking at us."

Tony nodded. "Yeah. I've been meaning to catch some sleep, but it's interesting-"

"You won't get a chance to sleep," Bonner said. "I've been reviewing your plan to get Sanders out of jail. I like it."

Tony eyed him warily.

"It seems to me this is a good time," Bonner said. "While everyone's watching us. You did say weekend, and this is Saturday."

Oh shit oh dear, Tony thought. "But we don't need to. Not after this! Everybody will know we really need defenses ... "

"What happened today won't change the fact that the kids Pres killed were carrying nothing more deadly than sand and paint. This may make it easier to get a jury to acquit him, but he'll still have put in a year in jail before it's over."

"And Pres? Have you asked him about this?" Tony demanded.

Bonner ignored the question. "Your plan needs some advance preparations," Bonner said. "As near as I can figure, if you start now, we can be ready tonight at lights-out. Any reason why you can't get to it?"

"Conspiracy," Tony said. "And if anyone's killed, it's homicide-"

"So don't kill anyone. You've already made up your mind, Tony. I don't have to wheedle you. So let's cut the crap and get at it. We both have work to do."

Tony nodded in submission.

XVIII. EXECUTIVE ACTION

When we jumped into Sicily, the units became separated, and I couldn't find anyone. Eventually I stumbled across two colonels, a major, three captains, two lieutenants, and one rifleman, and we secured the bridge. Never in the history of war have so few been led by so many.

-General James Gavin

George Harris had learned to disconnect his mind during heavy exercise. If he thought about the pain or the fatigue or the monotony, he'd stop. His body followed the routine while his mind daydreamed, or planned business strategy, or slept.

But on Saturdays and Sundays, shut away from his weights and machines and confined by concrete and iron bars, he had to improvise a routine. That took concentration. It took more concentration to ignore a distraction, the sad-eyed ghost in the upper bunk.

Twenty-nine ... thirty. Harris rested for a few seconds, waiting until his breathing slowed before he spoke. A harmless vanity. Then, "I wish to hell you'd join me. You're in good shape. What were you doing on the outside, skiing? Surfing? You're not doing it now. In here I've never seen you do anything but lie there and eat your liver."

Preston Sanders didn't look up. His arms were behind his head, his eyes were on the ceiling.

"That raid last night has to help your case," Harris said. "They

had real bombs, and the TV said there was a shootout. Guns and everything. This wasn't just kids out playing tricks."

Still nothing. "Now there's demonstrations all over the city. Fromates and a lot of outfits named Citizens for This and That want to burn Todos Santos to the ground and sow salt where it stood. Funny thing, though. There are counter-demonstrators. Nothing organized, but more than you'd expect." George went into his sit-ups. The patrolling guard stopped for a minute to watch, then moved on. On previous weekends he'd made witty comments ... until George called him "Butterball" every time he passed, and then every felon in the block took it up, and now the guard generally didn't say anything.

Thirty. George stood and went to the bunks. "You lie there long enough and you'll turn to butter," he told Sanders. "Jesus, you're younger than I am. Can you do thirty push-ups?"

''No."

"It'd take your mind off what's eating you. Sanders, it is impossible to think about what a jury will do to you when you're on your twenty-fifth push-up and going for thirty. Try it with me?"

Sanders shook his

head.

He was the least troublesome cell-mate George Harris had ever had. More: He was a potential customer, even if he did turn off whenever George tried to swing the conversation around to new construction in Todos Santos. I guess I brought it up too early, George thought. Too bad, but maybe that'll change. If I can get him to talk at all, and that's tough enough.

"They didn't identify the raiders yet," Harris said. "But that commentator guy, Lunan, said they were an outfit calling itself the American Ecology Army. That's a splinter group that broke away from the Fromates years ago, but Lunan says the two outfits still work together. He sounded real sure. I read everything I can about it, what with being in here with you. Besides, I knew the Planchet kid."

That got Sanders's attention. "I never did. What was he like?"

Harris shrugged. "Nice enough, I guess. Personable, maybe a little shy. I only met him twice. I could have liked him, except I heard about a stunt he pulled in high school. Never mind. The point is, he was a total damned fool and he died for it."

"He didn't die. He was killed."

"Yeah, sure, but he worked at it. Hey, you know you're a hero back in Todos Santos? Yeah, no kidding. I went to the Big Brothers lunch out there last week-"

"I always liked those."

"Yeah, I can see why. Quite a blast. I won a pocket computer in the raffle. Anyway, when they found out I was your cell-mate everybody wanted me to give you the same message. 'You done good.'"

"Who?" Sanders asked. "Art Bonner?"

"Yeah, he was one of them. Some others, too, I didn't get everybody's name. And Tony Rand." Harris looked sidewise at Sanders. "He's a strange one, isn't he?"

"He can be," Sanders said. "Tony's about the best friend I have out there."

"Oh, I can see how you could like that guy a lot. Once you got to know him. Anyway, they're all on your side. Sanders, it's dumb to lie there eating your liver. You got paid to do a job, and when the time came you earned your salary. You don't need to hear that from a jury. Think of it as evolution in action."

"What did you say?"

Harris laughed. "I saw it on-" He stopped. Listened. Then he said, "Get down from there. I mean it. Sit on the lower bunk. I think-" He listened again. "Feel that? I think there's a quake coming." He tugged at Sanders's arm, and Sanders came down. He wasn't that soft; he didn't drop, he lowered himself by the strength of his arms.

Harris said, "You feel it? Not a jolt, just shaking, like a preliminary temblor? Everything's vibrating-"

"I feel it."

"I hear something, too." It was right at the threshold of sound but it went on, steadily.

"Machinery somewhere," Sanders said. "You're not from California, are you? Earthquakes can't be heard coming."

"Wha ... ? Oh. Too bad." Harris considered going into deep knee bends; but by damn, he'd finally got Sanders talking, and he wasn't going to stop. "What I saw was a bumper sticker. 'RAISE THE SPEED LIMIT. THINK OF IT AS EVOLUTION IN ACTION."

Sanders smiled. "I can guess who said that first. It had to be Tony Rand."

"Really? I wouldn't have guessed that. I mean, I didn't get to talk to him very long, but I was impressed, meeting the guy that built the Nest." Aaargh. Wrong word, it had just slipped out. In haste, Harris continued, "What's he really like?"

"A good friend," Sanders said. "He didn't used to worry much about social relationships, politics, anything like that. Now he's eating his liver, like you said. He's losing sleep because maybe he could have designed Todos Santos so I wouldn't have to do that." Sanders shuddered, and Harris was suddenly afraid there would be histrionics. But Sanders said quietly, "Maybe he's keeping me sane. Damn, I'd love to blame it all on Tony Rand. And I know he never thought of that. I know it. That's the nice part."

"Court magician," Harris said. "That's what they called him on the TV documentary, anyway." And I've got you talking now- Only a miracle could have captured Harris's attention at that moment.

The miracle was a tiny hole that formed suddenly in the concrete floor, just where Harris's eyes rested. George slid off the bunk and crouched to look. He poked at the hole with his finger. It was real.

Sanders asked, "What are you doing?"

"Damndest thing," Harris said. He thought he saw light through the hole, but when he bent closer to look, there was only darkness. And a trace of a strange, mustily sweet smell. "Orange blossoms? I saw this little tiny," he said, and fell over.

The vehicle Tony Rand was driving was longer than four Cadillacs, and shaped roughly like a .22 Long Rifle cartridge. Thick hoses in various colors, some as thick as Tony's torso, trailed away down the tunnel and out of sight. The visibility ahead was poor. The top speed was contemptible. The mileage would have horrified a Cadillac owner. It wasn't even quiet. Water poured through the blue hoses, live steam blasted back down the red hoses, hydrogen flame roared softly ahead of the cabin, heated rock snapped and crackled, and cool air hissed in the cabin.

For so large a vehicle the cabin was cramped, stuck onto the rear almost as an afterthought. It was cluttered with the extra gear Tony Rand had brought with him, so that Thomas Lunan had to sit straddling a large red-painted tank and regulator. There were far too many dials to watch. The best you could say for the Mole was that, unlike your ordinary automobile, it could drive through rock.

So we're driving through rock, Lunan thought, and giggled. The blunt, rounded nose of the Mole was white hot. Rock melted and flowed around the nose, flowed back as lava until it reached the water-cooled collar, where it froze. The congealed rock was denser then, compressed into a fine tunnel wall with a flat floor.

Lunan was sweating. Why did I get into this? I can't get any pix, and I can't ever tell anybody I was here.

"Where are we?" Lunan asked. He had to shout.

"About ten feet to go," Rand said.

"How do you know?"

"Inertial guidance system," Rand said. He pointed to a blue screen, which showed a bright pathway that abruptly became a dotted line. "We're right here," Tony said. He pointed to the junction of dot and solid line.

"You trust that thing?"

"It's pretty good," Rand said. "Hell, it's superb. It has to be. You don't want to put a tunnel in the wrong place."

Lunan laughed. "Let's hope they want a tunnel here-"

"Yeah." Rand fell silent. After a while he adjusted a vent to increase the cool air flowing through the cabin.

Despite the air flow, and the cabin insulation, Lunan was sweating. There was no place to hide. None at all. If anyone suspected what they were doing, they had only to follow the hoses to the end of the blind tunnel.

"We're here," Rand said.

Noise levels fell as Rand turned down the hydrogen jets. He looked at his watch, then lifted the microphone dangling from the vehicle's dashboard. "Art?"

"Here."

"My computations tell me I'm either under Pres's cell or just offshore from Nome, Alaska-"

"You don't have to keep me entertained." The voice blurred and crackled. No eavesdropper could have sworn that Art Bonner was speaking to the soon-to-be-notorious felon, Anthony Rand. A nice touch, Lunan thought.

"No, sir," Tony said.

"As far as we can tell, you hit it just right," the radio said. "They're still at dinner. Or all the months of tunnel drilling around here got them used to the noise. Whatever. Anyway, we don't hear any signs of alert."

"Good," Rand said. He put down the microphone and turned to Lunan. "Now we wait four hours."

Lunan had carefully prepared for this moment. He took a pack of cards from his pocket and said, casually: "Gin?"

It was nine-thirty in the evening and Vinnie Thompson couldn't believe his good fortune. He'd been hoping for a decent score later, some guy coming back from winning a big bet on the hockey game at the Forum, or maybe a sailor with a month's pay. This early there probably wouldn't be much, but there might be somebody with bread, although most Angelinos were smart enough not to carry much into the subway system. Of course

they'd carry money in the Todos Santos stations, but everybody in Vinnie's line of work learned early to stay away from there. The TS guards might or might not turn you in to the LA cops, but more important they might hurt you. A lot. They didn't like muggers at all.

Maybe tonight he'd get a break. He needed one. He hadn't hit a good score in two weeks.

Then he saw his vision. A man in a three-piece suit, an expensive suit with alligator shoes (like the ones Vinnie kept at home, you wouldn't catch him taking something valuable like that into the subway). The vision carried a briefcase, and he was not only alone, he'd gone through a door into a maintenance tunnel!

The Integral Trees - Omnibus

The Integral Trees - Omnibus A World Out of Time

A World Out of Time Crashlander

Crashlander The World of Ptavvs

The World of Ptavvs Ringworld

Ringworld Juggler of Worlds

Juggler of Worlds The Ringworld Throne

The Ringworld Throne The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic

The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic A Gift From Earth

A Gift From Earth Escape From Hell

Escape From Hell Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII Rainbow Mars

Rainbow Mars Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I Destroyer of Worlds

Destroyer of Worlds Man-Kzin Wars XIV

Man-Kzin Wars XIV Treasure Planet

Treasure Planet N-Space

N-Space Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition

Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition The Ringworld Engineers

The Ringworld Engineers Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII The Magic May Return

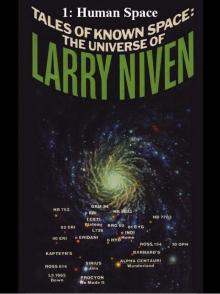

The Magic May Return Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven

Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven The Magic Goes Away

The Magic Goes Away Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI Man-Kzin Wars III

Man-Kzin Wars III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI Inferno

Inferno 01-Human Space

01-Human Space Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton

The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton Ringworld's Children

Ringworld's Children Man-Kzin Wars XII

Man-Kzin Wars XII Scatterbrain

Scatterbrain Man-Kzin Wars 9

Man-Kzin Wars 9 Man-Kzin Wars XIII

Man-Kzin Wars XIII Flatlander

Flatlander Man-Kzin Wars V

Man-Kzin Wars V Destiny's Forge

Destiny's Forge Scatterbrain (2003) SSC

Scatterbrain (2003) SSC The Time of the Warlock

The Time of the Warlock Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II

Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9)

Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9) Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8)

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8) Treasure Planet - eARC

Treasure Planet - eARC The Draco Tavern

The Draco Tavern Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti The Fourth Profession

The Fourth Profession Betrayer of Worlds

Betrayer of Worlds Convergent Series

Convergent Series Starborn and Godsons

Starborn and Godsons Protector

Protector Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4)

Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4) The Legacy of Heorot

The Legacy of Heorot 03-Flatlander

03-Flatlander Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII Destiny's Road

Destiny's Road Fate of Worlds

Fate of Worlds Beowulf's Children

Beowulf's Children 04-Protector

04-Protector The Flight of the Horse

The Flight of the Horse Man-Kzin Wars IV

Man-Kzin Wars IV The Moon Maze Game dp-4

The Moon Maze Game dp-4 The California Voodoo Game dp-3

The California Voodoo Game dp-3 07-Beowulf Shaeffer

07-Beowulf Shaeffer Ringworld's Children r-4

Ringworld's Children r-4 The Man-Kzin Wars 05

The Man-Kzin Wars 05 The Man-Kzin Wars 12

The Man-Kzin Wars 12 Lucifer's Hammer

Lucifer's Hammer The Seascape Tattoo

The Seascape Tattoo The Moon Maze Game

The Moon Maze Game Man-Kzin Wars IX

Man-Kzin Wars IX All The Myriad Ways

All The Myriad Ways More Magic

More Magic 02-World of Ptavvs

02-World of Ptavvs ARM

ARM The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld)

The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld) Burning Tower

Burning Tower The Man-Kzin Wars 06

The Man-Kzin Wars 06 The Man-Kzin Wars 03

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC

Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC The Hole Man

The Hole Man The Warriors mw-1

The Warriors mw-1 The Houses of the Kzinti

The Houses of the Kzinti The Man-Kzin Wars 07

The Man-Kzin Wars 07 The Man-Kzin Wars 02

The Man-Kzin Wars 02 The Burning City

The Burning City At the Core

At the Core The Trellis

The Trellis The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1 The Man-Kzin Wars 04

The Man-Kzin Wars 04 The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names

The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names Dream Park

Dream Park How the Heroes Die

How the Heroes Die Oath of Fealty

Oath of Fealty The Smoke Ring t-2

The Smoke Ring t-2 06-Known Space

06-Known Space Destiny's Road h-3

Destiny's Road h-3 Flash crowd

Flash crowd The Man-Kzin Wars 11

The Man-Kzin Wars 11 The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014

The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014 The Ringworld Throne r-3

The Ringworld Throne r-3 A Kind of Murder

A Kind of Murder The Barsoom Project dp-2

The Barsoom Project dp-2 Building Harlequin’s Moon

Building Harlequin’s Moon The Gripping Hand

The Gripping Hand The Leagacy of Heorot

The Leagacy of Heorot Red Tide

Red Tide Choosing Names mw-8

Choosing Names mw-8 Inconstant Moon

Inconstant Moon The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War

The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld

Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld Ringworld r-1

Ringworld r-1 05-A Gift From Earth

05-A Gift From Earth The Integral Trees t-1

The Integral Trees t-1 Footfall

Footfall The Mote In God's Eye

The Mote In God's Eye Achilles choice

Achilles choice The Man-Kzin Wars 01

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 Procrustes

Procrustes The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3 The Goliath Stone

The Goliath Stone The Man-Kzin Wars 09

The Man-Kzin Wars 09