- Home

- Larry Niven

Juggler of Worlds Page 4

Juggler of Worlds Read online

Page 4

The big disparity was in manes. Passing from worker to worker—up the corporate ladder?—mane styles became ever more elaborate. Like the aristo Wunderlander beards, an elaborate mane style denoted social status. This boss Puppeteer, Sigmund decided, his mane resplendent, will be Adonis.

“Again, Mr. Ausfaller, I do not understand UN interest.”

You conniving weasel, Sigmund thought. Perhaps one new human spaceship in 20 isn’t built in an exorbitantly priced General Products hull, reliant on claims of invulnerability.

Adonis stepped out from behind his melted-looking desk. He gave a wide berth to the row of human chairs, and the “dangerous” edges on their legs. To show Sigmund the exit?

Sigmund said, “It has come to our attention that a Sol system citizen died recently in a GP-supported experiment.” Not that there were Sol system citizenships, but it sounded plausible, and Peter Laskin had been a Belter.

“Ah, the Laskins.” The Puppeteer lightly pawed the floor with one forehoof. “I’m now doubly surprised. Their ship was only very recently recovered. A tragedy, to be sure.”

Other ARMs had studied Puppeteers. Pawing the floor was believed to be a flight reflex.

Hyperwave radio was a wonderful thing. It was instantaneous where it worked: everywhere except deep within gravity wells. Comm buoys in the comet belts of all settled solar systems converted between radio waves and laser beams for intrasystem messaging and hyperwaves for interstellar messaging.

The ARM placed a very high priority on infiltrating General Products. Did Adonis suspect? How surprised would he be to know Raul Miller secretly worked for the ARM? That while piloting the salvaged Hal Clement home from BVS-1 Miller reported back to Earth?

Thereafter, it made perfect sense that ARM HQ had notified Sigmund, already en route from Jinx to We Made It. Both Laskins held research grants from the Institute of Knowledge.

“Very tragic,” Sigmund agreed. He ignored Adonis’ implied question. “But their deaths are only a part of our concern. What most interests me is how they died inside one of General Products’ supposedly impregnable hulls.”

THE PUPPETEER PROFESSED bafflement.

His idiom and accent were flawless. Sigmund did not doubt the Puppeteer’s acting skills. “Show me the ship,” Sigmund demanded.

“Why not.” The Puppeteer looked himself in the eyes again. “We also want to understand what happened. If you can explain, so much the better. Come with me.”

Adonis had a transfer booth in his office. They stepped through. Outside the destination booth, a spaceship rested on its side. It was about one hundred meters long and pointed at both ends. General Products sold only four hull versions; this was the #2 model. One end was painted, the rest left transparent, just as it—as all GP hulls—had been delivered.

Then Sigmund made the mistake of looking up.

We Made It was among the most inhospitable of the human-settled worlds. Summers and winters, the surface winds approached 250 kilometers per hour. The colonists built underground.

Hotels catering to the tourist trade had gravity generators. Elsewhere there was no ignoring the paltry gravity, a mere six-tenths gee, or the Belter-gangly natives, but Sigmund could—and did—stay indoors.

This wasn’t a hangar.

He stood on a ground-level roof. The ship was the only structure of any kind. Featureless desert stretched to the horizon in every direction. Although it was spring, he couldn’t see even the smallest speck of greenery—seasonal winds scoured the land clean of life. In a too-bright sky, above the blazing, too-blue sun, hung the piercing red spark that was Procyon B.

His heart pounded. His hands shook. Sigmund told himself the crawling on his skin was only the arid desert air.

Eyes cast down, he strode toward the ship. Its hull was transparent, but massive apparatuses inside cast long shadows. He stopped for a closer look in a comforting pool of shade beneath the stern.

Things appeared—wrong. The landing shocks were bent. Panels and equipment looked like they had melted and been forced aft under tremendous pressure.

A gust of wind flapped Sigmund’s trousers. Dust and gravel spattered off the hull. The breeze smelled—wrong. He hurried into the air lock.

He was in the main crew quarters when Adonis joined him. Something had torn loose the acceleration couches and sent them crashing into the ship’s nose. Instruments and chairs alike had crumpled. Walls, decks, ceiling—everything toward the bow—were thickly spattered in something brown.

Sigmund knew the answer before he asked. “These brown splashes?”

“That,” said the Puppeteer, “is the Laskins.”

ALIEN SKY SUDDENLY didn’t feel like a problem. Gulping, Sigmund walked back to the air lock. He and Adonis cycled through.

In the windbreak under the hull, Sigmund demanded, “What did that?”

The Puppeteer plucked at his mane. “Are you familiar with BVS-1?”

“No,” Sigmund lied. Until recently, the statement would have been true. Since Raul Miller’s relayed message, though, Sigmund had read everything on the subject that he could find.

“An old, dead neutron star, scarcely a light-year away, recently discovered by the Institute of Knowledge. They wished to study it up close, but lacked funding. We offered them a suitable ship, with the usual guarantees, if they shared their findings.”

Having died, the Laskins weren’t sharing.

The Puppeteer was suddenly at a loss for words. Bit by bit, Sigmund coaxed out the story. Nothing contradicted the report from Miller: Prepping the Hal Clement on We Made It, because Peter Laskin, a Belter, refused to set foot on Jinx. The short flight to BVS-1. The initial, unremarkable observations from a distance, reported by hyperwave. The suspension-become-cessation of communications for the dive into the singularity. Whatever the Laskins learned, lost. The rescue turned salvage mission.

GP hulls were supposedly indestructible. Nothing got through but visible light—customers painted any parts they wanted opaque. And if it was learned that mysterious forces could kill right through the hulls? Sigmund understood Adonis’ dilemma. General Products might be ruined.

Not his problem.

This was: Suppose the Institute of Knowledge suspected this vulnerability. Suppose the so-called research project was somehow a test of a Jinxian weapon. He imagined death rays that penetrated the hulls of Earth’s fleet, impregnable no more.

“What did this?” Sigmund hissed.

“We do not know.” More pawing at the ground. “As you can imagine, we very much desire an explanation. As you might also imagine, no one, for any amount of money, will repeat the Laskins’ voyage.”

Didn’t know? Sigmund refused to accept that.

To believe what little they disclosed about themselves, Puppeteers were herbivores and herd animals. To those who felt kindly toward them, the Puppeteers were supremely cautious. Everyone else called the aliens cowards—and Puppeteers took that as a compliment.

They nonetheless sold supposedly impregnable hulls to other races. Those sales might reflect unshakable confidence that their worlds would never be revealed. It seemed far more likely they had secret ways to disable any of their own hulls turned against them.

Wind whipped around the hull and clutched at Sigmund’s clothes. The feeble pull of this world seemed unequal to the task of holding him down. Stubbornly, Sigmund denied his fear.

Whether or not Adonis truly sought answers, he must cooperate fully with an ARM investigation. Anything less would show General Products already understood the undisclosed vulnerability—and sold the hulls regardless.

Something about Sigmund’s flight to We Made It prodded his subconscious. Pamela? Vurguuz?

Overcrowding. “Have you asked pilots laid off by Nakamura Lines?”

“Among others,” Adonis said. “All have declined. Their reticence, however problematical, is logical. Assuring their silence thereafter has cost us a small fortune.”

Once more, Sigmund pictured an enemy

fleet equipped with whatever slaughtered the Laskins without harm to their ship’s hull. Jinxians. Kzinti. Belters. The adversary hardly mattered. What was intolerable was Earth’s sudden exposure.

The ARM had resources Puppeteers did not. “If I find a volunteer, I trust you’ll provide us a ship on the same terms you offered the Jinxians.”

It wasn’t a question, because Adonis had no choice.

6

Sigmund had his pilot, although to call Beowulf Shaeffer a volunteer was a stretch.

At Sigmund’s insistence, General Products made Shaeffer the same offer 11 pilots had earlier rejected. Shaeffer made that an even dozen.

And then Shaeffer, too, discovered he had no choice.

Sigmund had selected Shaeffer by data mining the financial records of out-of-work pilots. On Earth, Sigmund would have completed such a search in minutes. Here on We Made It, it could have been done almost as quickly with a bit of hacking. Instead, he obtained access from the local authorities. Professional courtesy (although not total candor).

Interstellar cruise lines paid their pilots well, and Shaeffer chose to maintain his standard of living after the Nakamura Lines folded. Now, months later, Shaeffer was mired in debt. Despite the artfulness with which he fudged his loan applications, rolled old debts over into new loans, and dribbled out partial payments to his creditors, the moment of financial truth loomed.

A million stars or debtor’s prison—that was the offer Sigmund had advised Adonis to extend.

For two weeks, Sigmund had kept watch from a discreet distance. Shaeffer spent his days here in the GP building, supervising the Puppeteer engineers configuring a new #2 hull to his specifications. He’d named his ship Skydiver. Tomorrow, Shaeffer left.

I had no choice, Sigmund told himself. If not Shaeffer, then whom?

Sigmund had followed Shaeffer into the GP tavern. Its clientele were mostly Puppeteers. The barroom chatter sounded like dueling orchestras warming up.

Shaeffer grew up on We Made It. He stood well over two meters tall, merely average here. He massed about 70 kilos, scrawny by Earth standards but stocky for a local. Commercial spaceships generally maintained artificial gravity at a standard gee; Shaeffer must have worked out to handle the gravity aboard his own ship. Like many on this planet of mole people, he was an albino.

One other thing about Shaeffer—he had a mind of his own.

And so Sigmund kept postponing this conversation. It was better that Shaeffer maintain his illusion of free will.

Sigmund crossed the bar. Without asking, he sat at Shaeffer’s table. Shaeffer’s face froze, and he shoved back his chair and stood.

“Sit down, Mr. Shaeffer,” Sigmund said.

“Why?”

Sigmund offered his ARM badge. Shaeffer tilted the disc this way and that. From the time he devoted to the task, he was stalling. “My name is Sigmund Ausfaller. I wish to say a few words concerning your assignment on behalf of General Products.”

Shaeffer stayed.

“A record of your verbal contract was sent to us as a matter of course,” Sigmund said. That sounded better than: I set you up. “I noticed some peculiar things about it. Mr. Shaeffer, will you really take such a risk for only five hundred thousand stars?”

“I’m getting twice that.”

“But you only keep half of it. The rest goes to pay debts. Then there are taxes. . . . But never mind. What occurred to me was that a spaceship is a spaceship, and yours is very well armed and has powerful legs.” The planned armaments had struck Sigmund as soon as Adonis passed along Shaeffer’s specs. Without knowing what had killed the Laskins, weapons made sense. But defense wasn’t the only explanation. “An admirable fighting ship, if you were moved to sell it.”

“But it isn’t mine.”

“There are those who would not ask. On Canyon, for example. Or”—Sigmund theatrically stroked the spike of his beard—“the Isolationist party of Wunderland.”

Shaeffer said nothing, but metaphorical wheels turned behind those spooky red eyes. No doubt about it—he’d thought of running.

Unacceptable. Earth was in danger; it needed a pilot. Sigmund pressed on. “Or you might be planning a career of piracy. A risky business, piracy, and I don’t take the notion seriously.” The hell he didn’t.

“What I would like to say is this, Mr. Shaeffer. A single entrepreneur, if he were sufficiently dishonest, could do terrible damage to the reputation of all human beings everywhere. Most species find it necessary to police the ethics of their own members, and we are no exception. It occurred to me that you might not take your ship to the neutron star at all, that you would take it elsewhere and sell it. The Puppeteers do not make invulnerable war vessels. They are pacifists. Your Skydiver is unique.”

More lies, of course. Planetary governments outfitted GP hulls as warships all the time. Skydiver was unique nonetheless—a warship about to be released into the control of a single civilian. Judging by his run-up of debt, Shaeffer didn’t mind cutting a few corners. . . .

In the cause of Earth’s defense, neither did Sigmund. “Hence, I have asked General Products to allow me to install a remote-control bomb in Skydiver. Since it is inside the hull, the hull cannot protect you. I had it installed this afternoon.

“Now, notice! If you have not reported within a week, I will set off the bomb. There are several worlds within a week’s hyperspace flight of here, but all recognize the dominion of Earth. If you flee, you must leave your ship within a week, so I hardly think you will land on a nonhabitable world. Clear?”

Shaeffer stiffened. After a long while he said, softly, “Clear.”

“If I am wrong, you may take a lie-detector test and prove it. Then you may punch me in the nose, and I will apologize handsomely.”

Shaeffer shook his head.

Feeling only twinges of guilt, Sigmund stood and walked from the bar.

7

Through surveillance cameras, Sigmund watched Shaeffer float between sleeping plates. He wasn’t sleeping. Shaeffer’s hands and face were flaming red and blistered. Whether from sunburn—how, from a cold, dead star, eluded Sigmund—or other reasons, his newly returned pilot was obviously in pain.

The man belonged in an autodoc, or at least pumped full of painkiller. This once, Adonis refused Sigmund’s demands. “Answers, first,” the Puppeteer said. Turning his back on Sigmund, Adonis cantered next door into the sickroom.

Shaeffer looked up. “What can get through a General Products hull?”

“I hoped you would tell me.” The room lacked Puppeteer furniture. Adonis leaned back on his single hind leg, looking ill at ease.

“And so I will. Gravity.”

“Do not play with me, Beowulf Shaeffer. This matter is vital.”

“I’m not playing,” Shaeffer said. “Does your world have a moon?”

“That information is classified,” Adonis replied. Any other answer would have shocked Sigmund.

Shaeffer’s shrug became a wince. “Do you know what happens when a moon gets too close to its primary?”

“It falls apart.”

“Why?”

“I do not know,” Adonis said. Nor, for that matter, did Sigmund.

“Tides.”

“What is a tide?” the Puppeteer asked.

Sigmund started. A very interesting piece of data had just fallen into his lap.

It seemed Shaeffer had gotten it, too. He was quiet for a long time. “I’m going to try to tell you. The Earth’s moon is almost thirty-five hundred kilometers in diameter and does not rotate with respect to Earth. I want you to pick two rocks on the moon, one at the point nearest the Earth, one at the point farthest away.”

“Very well,” Adonis said.

“Now, isn’t it obvious that if those rocks were left to themselves, they’d fall away from each other? They’re in two different orbits, mind you, concentric orbits, one almost thirty-five hundred kilometers outside the other. Yet those rocks are forced to move at the same orbital speed.”

“The one outside is moving faster.”

“Good point,” Shaeffer acknowledged. “So there is a force trying to pull the moon apart. Gravity holds it together. Bring the moon close enough to Earth and those two rocks would simply float away.”

“I see. Then this ‘tide’ tried to pull your ship apart. It was powerful enough in the lifesystem of the institute ship to pull the acceleration chairs out of their mounts.”

“And to crush a human being. Picture it. The ship’s nose was just a few kilometers from the center of BVS-1. The tail was a hundred meters farther out. Left to themselves, they’d have gone in completely different orbits. My head and feet tried to do the same thing when I got close enough.”

Sigmund’s mind flashed to the recovered video from cameras hidden aboard Skydiver, video hastily scanned as GP personnel settled Shaeffer in next door.

Water bulbs, clipboards, voice recorder, all the loose paraphernalia on the bridge, shifting and vibrating as though with minds of their own. The panicked look on Shaeffer’s face as understanding struck. His doomed attempts to pull out of the ship’s hyperbolic plunge. His mad scramble up the main access tube to the ship’s center of gravity, where tidal effects would be almost nil. Shaeffer spread-eagled, his spider-like limbs atremble, pressing against the smooth sides of the access tube. Slipping, slipping . . .

Starlight blazing brighter and brighter through the transparent hull as the ship plummeted toward the neutron star: gravitational lensing. Hah! That was the cause of the sunburn.

In the vacated cabin, those same water bulbs, clipboards, voice recorder now, one by one, hurtling into the bow. The impregnable hull ringing like a gong with each blow. Acceleration couches ripping loose to follow, each collision tolling like a great cathedral bell.

Shaeffer slipping, slipping, a muscle tremor away from plummeting half the ship’s length—splat!—to join them.

But Shaeffer had only almost been torn loose, torn apart, to be daubed like paint across the ship’s bow. That’s why Shaeffer was in such pain.

The Integral Trees - Omnibus

The Integral Trees - Omnibus A World Out of Time

A World Out of Time Crashlander

Crashlander The World of Ptavvs

The World of Ptavvs Ringworld

Ringworld Juggler of Worlds

Juggler of Worlds The Ringworld Throne

The Ringworld Throne The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic

The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic A Gift From Earth

A Gift From Earth Escape From Hell

Escape From Hell Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII Rainbow Mars

Rainbow Mars Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I Destroyer of Worlds

Destroyer of Worlds Man-Kzin Wars XIV

Man-Kzin Wars XIV Treasure Planet

Treasure Planet N-Space

N-Space Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition

Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition The Ringworld Engineers

The Ringworld Engineers Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII The Magic May Return

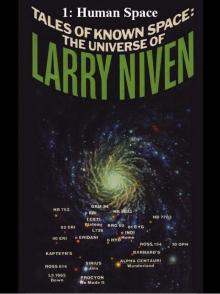

The Magic May Return Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven

Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven The Magic Goes Away

The Magic Goes Away Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI Man-Kzin Wars III

Man-Kzin Wars III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI Inferno

Inferno 01-Human Space

01-Human Space Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton

The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton Ringworld's Children

Ringworld's Children Man-Kzin Wars XII

Man-Kzin Wars XII Scatterbrain

Scatterbrain Man-Kzin Wars 9

Man-Kzin Wars 9 Man-Kzin Wars XIII

Man-Kzin Wars XIII Flatlander

Flatlander Man-Kzin Wars V

Man-Kzin Wars V Destiny's Forge

Destiny's Forge Scatterbrain (2003) SSC

Scatterbrain (2003) SSC The Time of the Warlock

The Time of the Warlock Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II

Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9)

Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9) Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8)

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8) Treasure Planet - eARC

Treasure Planet - eARC The Draco Tavern

The Draco Tavern Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti The Fourth Profession

The Fourth Profession Betrayer of Worlds

Betrayer of Worlds Convergent Series

Convergent Series Starborn and Godsons

Starborn and Godsons Protector

Protector Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4)

Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4) The Legacy of Heorot

The Legacy of Heorot 03-Flatlander

03-Flatlander Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII Destiny's Road

Destiny's Road Fate of Worlds

Fate of Worlds Beowulf's Children

Beowulf's Children 04-Protector

04-Protector The Flight of the Horse

The Flight of the Horse Man-Kzin Wars IV

Man-Kzin Wars IV The Moon Maze Game dp-4

The Moon Maze Game dp-4 The California Voodoo Game dp-3

The California Voodoo Game dp-3 07-Beowulf Shaeffer

07-Beowulf Shaeffer Ringworld's Children r-4

Ringworld's Children r-4 The Man-Kzin Wars 05

The Man-Kzin Wars 05 The Man-Kzin Wars 12

The Man-Kzin Wars 12 Lucifer's Hammer

Lucifer's Hammer The Seascape Tattoo

The Seascape Tattoo The Moon Maze Game

The Moon Maze Game Man-Kzin Wars IX

Man-Kzin Wars IX All The Myriad Ways

All The Myriad Ways More Magic

More Magic 02-World of Ptavvs

02-World of Ptavvs ARM

ARM The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld)

The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld) Burning Tower

Burning Tower The Man-Kzin Wars 06

The Man-Kzin Wars 06 The Man-Kzin Wars 03

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC

Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC The Hole Man

The Hole Man The Warriors mw-1

The Warriors mw-1 The Houses of the Kzinti

The Houses of the Kzinti The Man-Kzin Wars 07

The Man-Kzin Wars 07 The Man-Kzin Wars 02

The Man-Kzin Wars 02 The Burning City

The Burning City At the Core

At the Core The Trellis

The Trellis The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1 The Man-Kzin Wars 04

The Man-Kzin Wars 04 The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names

The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names Dream Park

Dream Park How the Heroes Die

How the Heroes Die Oath of Fealty

Oath of Fealty The Smoke Ring t-2

The Smoke Ring t-2 06-Known Space

06-Known Space Destiny's Road h-3

Destiny's Road h-3 Flash crowd

Flash crowd The Man-Kzin Wars 11

The Man-Kzin Wars 11 The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014

The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014 The Ringworld Throne r-3

The Ringworld Throne r-3 A Kind of Murder

A Kind of Murder The Barsoom Project dp-2

The Barsoom Project dp-2 Building Harlequin’s Moon

Building Harlequin’s Moon The Gripping Hand

The Gripping Hand The Leagacy of Heorot

The Leagacy of Heorot Red Tide

Red Tide Choosing Names mw-8

Choosing Names mw-8 Inconstant Moon

Inconstant Moon The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War

The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld

Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld Ringworld r-1

Ringworld r-1 05-A Gift From Earth

05-A Gift From Earth The Integral Trees t-1

The Integral Trees t-1 Footfall

Footfall The Mote In God's Eye

The Mote In God's Eye Achilles choice

Achilles choice The Man-Kzin Wars 01

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 Procrustes

Procrustes The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3 The Goliath Stone

The Goliath Stone The Man-Kzin Wars 09

The Man-Kzin Wars 09