- Home

- Larry Niven

Man-Kzin Wars XIV Page 5

Man-Kzin Wars XIV Read online

Page 5

“Very well, my friend and adviser. If you truly believe it is my duty and that I am needed, then I will do it, though it will sadden me greatly to take time from mathematics and history. And I rather think that if I go down this path, I shall have little time for anything else. What exactly must I do?”

Boniface smiled, as much as anyone ever does when facing a kzin. His mouth turned up at the corners and his eyes crinkled. “Thank you, my friend and one-time student. I believe it is the best thing for all of us on Wunderland that you do this. I shall put your name forward to the committee. They will have several candidates, I daresay, and the selection committee will interview all of them. I shall have to explain rather a lot of things to you.”

“So there is hope for me. The selection committee may reject me,” Vaemar reflected out loud.

“They might be that stupid. I don’t think so, but it is possible. It depends on the alternatives. You will, of course, do your best to get selected.”

“Yes, of course,” Vaemar said without any enthusiasm. And he would indeed have to do his best, any less would be dishonorable. Whatever doing his best might mean.

“What is it that makes this urgent?” Vaemar asked.

The abbot looked up at the silent stars. “Many small things. And just possibly one big thing. You know I have many sources of information, some not perhaps as reliable as others. And urgent is a word with many nuances.”

“I do not understand you,” Vaemar told him.

The abbot sighed. “There are some hints, some fragments which I have pieced together. I may be wrong. I hope I am.”

“Go on.”

“I have some reason to think there may be something out there. Further along the spiral arm. Something coming this way. You know, of the few sentient species in the galaxy that we have ever recorded, the thing I notice is how much we share. We can understand in some limited way what sort of things drive us. All men are brothers. Well, cousins at least, and we know this from genetics. But it goes deeper than that. You and I are very different in our genetics, but the universe has shaped us, and we have responded in ways which although different show striking similarities. We are both made up of star-stuff, both evolved in the Goldilocks Zone through similar sets of fantastic improbabilities. We both understand what truth and honor and justice mean, and they are important to both of us. You have your Fanged God, and we our Bearded God, but they might almost be two faces of the same entity. Both of them demand truth, honor and justice of us.”

“But your Bearded God also demands that you love your enemy,” the kzin rumbled softly. “And the Fanged God does not.”

“True,” Boniface admitted.

“Perhaps the Fanged God feared such a dreadful weapon being loosed in the universe.”

The abbot’s eyes lit. “Ah. You have seen that. Good. All the same, our response to the demands made upon us makes us almost brothers. And brothers, of course, fight and squabble with each other. But there may be something outside which is very different from all the species we know. Something terrible, something which threatens us all. And something which neither man nor kzin separately could face. It has been hinted to me that there is some sort of plan to forge a deeper alliance between our species, and perhaps others. Perhaps both our gods want that, and something acts for both of them. Perhaps because one day, perhaps a thousand years from now, we shall have to meet something so terrible that only a melding of the traditions of our people can hope to overcome it. The odds against our ships first encountering each other in the way they did were long indeed.”

“How stupid our telepaths were then, to discover you had no weapons but kitchen knives, and to miss entirely that your chief religious symbol was an instrument of torture!”

The abbot nodded to concede the point and then went back to his own. “Who knows what lies in wait for us, further up the spiral arm? You know how we got the hyperdrive: a race that lives in deep space—a race we knew nothing of—contacted our colony at Jinx and sold the colonists a manual. You know the size of space. Beyond your ability to imagine, or mine. Can that have been blind chance? I have heard a theory—no, less than a theory, a fingertip feeling—that our wars have been made by others, in order to forge in that flame some power that may be needed one day to defend truth and honor and justice and perhaps, yes, even love, and save them from something which would smash them as meaningless baubles and scatter the dust into endless night.”

There was a pause as man and kzin regarded each other calmly.

“One cannot make a life decision on mere speculation,” Vaemar rumbled.

“Of course not. But we have played enough chess, you and I, for you to know that it is foolish to make a move for only one reason. Strategy and tactics both are involved in making a move. The tactical issues are much easier to think about. But in the end, the strategy may be what makes a move into a winning game. And I sense that Wunderland may be the world on which man and kzin achieve something jointly which neither could hope for alone. Let that be no more than a dream, still it is a dream worth dreaming, don’t you think?

“There is another thing. Given that you are a reserve officer in our armed forces, and given that I have no hard facts to tell, I may tell you something else about this theory of mine: the telepaths have told us much that they never told you, their masters. Their range is short, but when one links to another, it is not so short. They cannot always correlate well, but when they do, the product is powerful. The telepaths have stores of secret knowledge. They do not, I think, know, but they have guessed—how, I know not—that something cataclysmic is happening in space.

“You know we offered Kzin a temporary truce so the kzinretti and kits on Wunderland left without . . . Heroes to care for them might be repatriated. It was . . . is . . . hoped that there might be more talks, leading to a permanent truce, though that may be but a dream. Still, our chief negotiator, McDonald, found out much—for the Patriarchy to talk to us at all is a huge step. It would never have happened if we had not gotten the hyperdrive and won the Liberation of this planet, along with Down and some other worlds. But we have discovered something you may find uncomfortable. The Patriarchy has found out about you, Vaemar.”

“I suppose they were bound to find out about me sooner or later,” Vaemar admitted.

“It was expected that their attitude would be berserk rage. But—forgive me if I use a monkey expression, for I do not mean to be insulting—it appears the Patriarch is no fool. In fact, his attitude appears to be something like ‘Lurk in the long grass. Wait and see.’ That must be our attitude too.”

“You so often give me things to think about. And so seldom anything easy.” Vaemar looked down at the little man who looked back at him with the hint of a smile on his lips. “You spoke of chess. Do I need to tell you, an Aspirant System Master, that you improve only by playing against better players?”

Dimity Carmody could see that Vaemar was unhappy with his decision. “I do understand, Vaemar,” she told him. “You are not the only mathematician to get mugged by reality. Remember, Gauss was a senior bureaucrat, and Evariste Galois died in a duel for political reasons. I guess mathematics and science are what are called ‘market failures’; most people are too dumb to see how important they are and don’t value them as much as pursuing power. At least you don’t fall into that set.”

“Thank you for seeing my dilemma and for being so understanding, Dimity. I had thought you would be angry with me.”

Dimity shook her head sadly. “Angry, yes, but not with you. With the dreadful fools we have to live among. And who can stay angry with them for long? After a short time it turns to pity, then a determination to have as little to do with them as possible. The trouble with politics started with Plato, who thought that our leaders should be selected from the best and brightest of the human race. Were he a bit more of a thinker and less of a literary man, he’d have realized that the best and brightest don’t want the job. They pursue insight, not power. Power is an empty piec

e of nonsense no intelligent person would waste time on. But that leads to power going to fools who want it, and they can make our lives a misery. So every so often, the intelligent must take control, however little they like the idea. And now is one of those times, I suspect. If the abbot thinks so, he is likely right. He has a lovely, simple mind, does Boniface. In a better world, he’d have been a mathematician. He has that hunger for the transcendent which is the mark of the best scientists and mathematicians.”

“Will I ever be able to go back to it, do you think?”

“Given that we can stop getting old in these times, I am sure you will, one day. As long as you stay playful, Vaemar. All the best work is play. And you may find enough in politics to stop you getting stodgy.

“The times constrain us, Vaemar, my love. How you put your mind to work is not a matter of personal preference. No man is an island, nor a kzin either. Mathematicians are ultimately the most practical of people; once you see things clearly there are no choices.”

Vaemar considered. He recalled that she had once pulled his tail playfully. Very few other beings could have done that and lived. But she saw everything with a terrible clarity and she saw his mind. She saw him as a mind; the outer form was not important to Dimity, just something to be played with. What Dimity said was right. There were no choices.

“Thank you, Dimity. You have opened doors for me into strange and wonderful worlds. And now the abbot has opened another, and I must pass through. But I will not forget the other worlds. Nor the joy of exploring them.”

“Come and see me when the need arises, Vaemar. When the squalor of engaging with mental and moral pygmies becomes too much to bear; when the pain of not being able to say what you think becomes intolerable, for fear of its effect on fools, I shall be here for you.”

“Where does it all come from?”

“There’s this little village, out in the boondocks. East of the range. Started off just after the kzin surrender, lots of people realized they’d starve to death without a government to organize bringing stuff into the city, and we hanged or shot most of the collabos. So some smart folk went out to do some farming and keep themselves in food. And some were already out there. Seems to have worked, there’s a whole collection of villages out there now, and the land around gets farmed and hunted.”

“But gold? And other stones?”

The trader shrugged. “There’s other stuff besides farming land. There’s a whole lot of country out there, some people just upped and grabbed their share of it. Like the Wild West in some of those old movies. Someone found the gold. There’s big seams of the stuff in quartz sometimes. And there are things pushed up from the deeps by volcanoes, plenty of those around. The abbey’s built on one.”

“And this comes from the other side of the abbey?”

“So they tell me.”

“Don’t you want to go off and get yourself some of that there gold?” The man was hungry. You could see it in his eyes.

“Nope. There’s other things out there besides gold. Like kzin hunters, who went out too, wanting to stay away from the conquerors, and with a mighty big grudge against humans, some of them. And other things, some of them as murderous as a kzin. The tigrepards and the lesslocks are bad enough, and the Morlocks, when they come out onto the surface at night, are worse. Me, I’m a city boy. Don’t fancy getting ate.”

“Still, if a bunch of guys, say a dozen of us with guns, was to go and find this place, we could get us our hands on some of the gold, maybe?”

“Maybe. And then again, maybe not. One of they kzin could take out a dozen men with his bare claws ’n’ fangs afore they could work out where to point the guns. Believe me, I’ve seen it. Thirty of us jumped a kzin during the war. I got away.”

“Can’t be much kind of law out there, yet,” the man argued. The trader could read him like a picture book, one with really dirty pictures. Yes, and a dozen armed men could find that village and take all that gold without having to do much digging at all, at all. Some people couldn’t abide work. He shrugged. No point in telling them the village was well armed. He remembered a psychopath in the early days of the Occupation, maddened by everything, a really nasty piece of work, who had enjoyed killing orphaned children. A kzin had decided the children were the Patriarch’s property. What had happened to the man had not been pleasant. This man, and his accomplices too, were the sort of people Wunderland would be better off without.

“I wouldn’t know. Like I said, I don’t want to get ate.”

This wasn’t quite true. The trader had spent some time yarning and exchanging gossip with the men and women and the odd kzin who had come in from the village. And he had heard of the judge. Judge Tom, the Law East of the Ranges. He sounded a tough cookie.

“Dimity Carmody says that you have a lovely, simple mind,” Vaemar told the abbot. He nodded.

“Yes, I do have a simple mind,” he admitted. “But it has taken me many years to get it that way. I think she was born with one, lucky girl.”

“She said that in a better world, you might yourself have been a mathematician. She said you have the hunger for transcendence which is the mark.”

“She would know. I have never seen myself that way. I feel myself to be too muddled, too confused. Still, it could be worse. I could be like so many people, who are so muddled and confused they haven’t even noticed they are muddled and confused. I give thanks to God that He has shown me something of the extent of my muddle and confusion. Just enough to see it and not so much as to make me despair. And now you have some questions about politics, I think.”

“Yes, some quite basic ones. For a start, why are there two political parties? What is special about two?” Vaemar was puzzled. He was stretched out before a roaring fire, polishing his ear-ring, while the abbot was sitting in a chair close by.

“I believe there was some mathematics developed about a century ago to consider that question, but it has puzzled others before you,” the abbot told him. He went on and started to sing in an artificial deep voice:

“I often think it’s comical, Fa la la, Fa la la,

“That every boy and every girl that’s born into this world alive,

“Is either a little liberal, or else a little conservative.

“Fa, la, la.”

The abbot looked quizically at Vaemar, who was astonished by what seemed to be unusual frivolity, even by human standards, and explained:

“That was written in the last part of the nineteenth century, so you are hardly the first person to find it puzzling. Gilbert’s guardsman did too. It has something to do with stability. You see, human beings have a good share of herd genes. Ninety-eight percent of our genes we have in common with chimpanzees, and about seventy percent we share with cows. And rather more with wolves. We have an impulse towards the collective. We also have an impulse towards hierarchical power structures, as do you kzin. We also have some who are individuals with a strong wish for freedom. These things are written inside us, and we all have something of them. In our various cultures, some of those impulses are expressed more freely than others, and get buttressed by memes.

“A political party is a coalition of memes, and these can change. For example, in Gilbert’s time, conservatives were generally much more collectivist and hierarchical, and the liberals much more individualist. In our day it is nearly the other way around, the conservatives are more inclined to individualism, the liberals are more collectivist. Of course, a coalition of individualists can be formed, but they tend to argue with each other rather a lot, so they are underrepresented in the political system. The individualists in the present conservative party are perhaps less individual and more hierarchical than those who vote for them.

“Of course, the general population has all these dispositions to different degrees. In any society, individuals learn that they have to cooperate to stay alive, and collectivists learn they have to be able to be independent sometimes. But the collectivist impulse ensures that people gather together wi

th those who think alike, that’s the nature of collectivism. And those who need freedom stay away from them, disliking the mutual coercion the collectivists habitually use on each other. But the individualists, too, need the support of a collective. They tend to feel ‘There is no such thing as society,’ because they make relatively few concessions for the approval of their partners. They expect to have to fight for what they want. The collectivist impulse means that an individual who has it strongly virtually lives for the approval of other members of the collective. Both are survival strategies, and are seldom met in their pure forms, but the genes are there, and the memes to express them in any culture.

“In stable times, the collectivist impulse can lead to mass hysteria, with the preference for believing things not because they are true but because you want to, or because your friends all do. These are not stable times, and believing things just because you want to can easily get you killed in a hostile environment, so there has been a strong selection pressure to be realistic. So the liberal party is not yet as dominated by ideology as it has been in the past, or as it will be again. It’s much more complicated than that, but it contains the essentials. So, there are two groups because human beings drift away from weaker collectives to more powerful ones. Not that two is always the necessary count of parties. Highly individualist cultures often have more, but then the groups themselves form coalitions. And fracture when the conflicting memes become too painfully apparent. People tend to vote as their parents do, sometimes seeing it as a matter of tribal loyalties rather than self-interest. There are other dimensions than the collectivism-individualism one of course, but that axis is important.

The Integral Trees - Omnibus

The Integral Trees - Omnibus A World Out of Time

A World Out of Time Crashlander

Crashlander The World of Ptavvs

The World of Ptavvs Ringworld

Ringworld Juggler of Worlds

Juggler of Worlds The Ringworld Throne

The Ringworld Throne The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic

The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic A Gift From Earth

A Gift From Earth Escape From Hell

Escape From Hell Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII Rainbow Mars

Rainbow Mars Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I Destroyer of Worlds

Destroyer of Worlds Man-Kzin Wars XIV

Man-Kzin Wars XIV Treasure Planet

Treasure Planet N-Space

N-Space Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition

Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition The Ringworld Engineers

The Ringworld Engineers Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII The Magic May Return

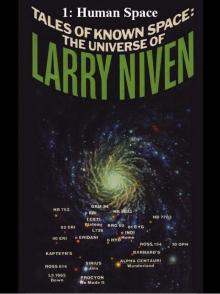

The Magic May Return Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven

Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven The Magic Goes Away

The Magic Goes Away Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI Man-Kzin Wars III

Man-Kzin Wars III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI Inferno

Inferno 01-Human Space

01-Human Space Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton

The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton Ringworld's Children

Ringworld's Children Man-Kzin Wars XII

Man-Kzin Wars XII Scatterbrain

Scatterbrain Man-Kzin Wars 9

Man-Kzin Wars 9 Man-Kzin Wars XIII

Man-Kzin Wars XIII Flatlander

Flatlander Man-Kzin Wars V

Man-Kzin Wars V Destiny's Forge

Destiny's Forge Scatterbrain (2003) SSC

Scatterbrain (2003) SSC The Time of the Warlock

The Time of the Warlock Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II

Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9)

Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9) Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8)

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8) Treasure Planet - eARC

Treasure Planet - eARC The Draco Tavern

The Draco Tavern Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti The Fourth Profession

The Fourth Profession Betrayer of Worlds

Betrayer of Worlds Convergent Series

Convergent Series Starborn and Godsons

Starborn and Godsons Protector

Protector Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4)

Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4) The Legacy of Heorot

The Legacy of Heorot 03-Flatlander

03-Flatlander Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII Destiny's Road

Destiny's Road Fate of Worlds

Fate of Worlds Beowulf's Children

Beowulf's Children 04-Protector

04-Protector The Flight of the Horse

The Flight of the Horse Man-Kzin Wars IV

Man-Kzin Wars IV The Moon Maze Game dp-4

The Moon Maze Game dp-4 The California Voodoo Game dp-3

The California Voodoo Game dp-3 07-Beowulf Shaeffer

07-Beowulf Shaeffer Ringworld's Children r-4

Ringworld's Children r-4 The Man-Kzin Wars 05

The Man-Kzin Wars 05 The Man-Kzin Wars 12

The Man-Kzin Wars 12 Lucifer's Hammer

Lucifer's Hammer The Seascape Tattoo

The Seascape Tattoo The Moon Maze Game

The Moon Maze Game Man-Kzin Wars IX

Man-Kzin Wars IX All The Myriad Ways

All The Myriad Ways More Magic

More Magic 02-World of Ptavvs

02-World of Ptavvs ARM

ARM The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld)

The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld) Burning Tower

Burning Tower The Man-Kzin Wars 06

The Man-Kzin Wars 06 The Man-Kzin Wars 03

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC

Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC The Hole Man

The Hole Man The Warriors mw-1

The Warriors mw-1 The Houses of the Kzinti

The Houses of the Kzinti The Man-Kzin Wars 07

The Man-Kzin Wars 07 The Man-Kzin Wars 02

The Man-Kzin Wars 02 The Burning City

The Burning City At the Core

At the Core The Trellis

The Trellis The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1 The Man-Kzin Wars 04

The Man-Kzin Wars 04 The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names

The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names Dream Park

Dream Park How the Heroes Die

How the Heroes Die Oath of Fealty

Oath of Fealty The Smoke Ring t-2

The Smoke Ring t-2 06-Known Space

06-Known Space Destiny's Road h-3

Destiny's Road h-3 Flash crowd

Flash crowd The Man-Kzin Wars 11

The Man-Kzin Wars 11 The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014

The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014 The Ringworld Throne r-3

The Ringworld Throne r-3 A Kind of Murder

A Kind of Murder The Barsoom Project dp-2

The Barsoom Project dp-2 Building Harlequin’s Moon

Building Harlequin’s Moon The Gripping Hand

The Gripping Hand The Leagacy of Heorot

The Leagacy of Heorot Red Tide

Red Tide Choosing Names mw-8

Choosing Names mw-8 Inconstant Moon

Inconstant Moon The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War

The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld

Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld Ringworld r-1

Ringworld r-1 05-A Gift From Earth

05-A Gift From Earth The Integral Trees t-1

The Integral Trees t-1 Footfall

Footfall The Mote In God's Eye

The Mote In God's Eye Achilles choice

Achilles choice The Man-Kzin Wars 01

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 Procrustes

Procrustes The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3 The Goliath Stone

The Goliath Stone The Man-Kzin Wars 09

The Man-Kzin Wars 09