- Home

- Larry Niven

The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War Page 7

The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War Read online

Page 7

I sat and thought. Van Roberts had a point. Indeed a better one than he realized: surely a spacefaring culture had to be both cooperative and scientific. Interstellar flight was not for primitives or for what had once been called savages.

Eating bodies? A different culture. It had taken humans a long time to understand the values of cetaceans who were relatively close kin. Dolphins could be savage and ruthless enough, and while their values and ethics were very real to them, studying and understanding them was the work of human lifetimes.

And it didn't, after all, hurt the dead to be eaten. Perhaps it was even some sort of compliment. I had read very recently of the Gallipoli campaign in the early twentieth century. The British and Australians had buried the dead, the Turks had left their bones to bleach on the ground which they had died to defend. Each side in a different way, the author said, was trying to honor them. Honor? It was an odd concept I had never got the hang of, except that it seemed to mean doing the right thing when things were difficult. But there was something more there.

And there had been another old classic author, the great Geoffrey Household himself, who had written that being eaten might be considered "the last offer of hospitality to a fellow hunter." After all, we were dealing with aliens. Maybe they had killed reluctantly, in self-defense, and eaten the dead to honor them. Maybe—for we had not lingered to investigate the sites thoroughly—those had not been pieces of human bone we had seen, or so I tried to tell myself briefly. But no, I was a professor of biology and knew a human femur when I saw one.

The creatures looked terrifying. So said the monks and the crew of the Angel's Pencil. Well, so did gorillas. And very nearly too late to save the last of the species, gorillas were found to be gentle, intelligent vegetarians, handicapped by lacking a voicebox. Right at the dawn of archaeology the shambling, bestial Neanderthals were found to have been altruistic, caring for grossly deformed and helpless individuals until they died at advanced ages, sometimes burying their dead poignantly with flowers.

Even carnivores that were bywords for savagery in Earth folklore, like wolves and killer whales, were found by scientific investigation to kill no more than they needed. Further, throughout nature on both planets some harmless creatures had evolved a threatening appearance as protection. And sometimes it worked the other way: our poison-fanged Beam's beast looked like a cuddly toy.

They had tried to cook the crew of the Angel's Pencil with some kind of heat induction ray. A tragically mistaken attempt to communicate? No alien had survived to explain. There had been Belters in the Pencil. Sol Belters, like our own Serpent Swarmers, were regarded by flatlanders as paranoid. I remembered an old lit. course story, a "sequel" by another author to H. G. Wells's late-nineteenth-century classic The Time Machine, which revealed that the horrible, cannibalistic Morlocks had in fact been benevolent scientists trying to communicate with the panic-stricken and homicidal time-traveler. And Wells himself had written of 1914: "Nothing could have been more obvious to the people of the early twentieth century than the rapidity with which war was becoming impossible." War and science did not go together, and, we were told, never had—until we started reading those old fragments. Appearances were against the felinoids, but... surely when humanity established its first interstellar colony it had brought with it some wisdom and experience, some humble recognition of past wrongs to other species and some sense of responsibility to the future? And I remembered that automatic gun twisted into scrap, and human bone in a puddle of blood.

"So what exactly are you saying?" I asked.

"These creatures could be allies in advancing democracy here. We should be communicating with them. Instead of which we are turning out panic-measure weapons. All right, let us say we know they react violently to provocation. Surely, Professor, you can see we may be standing on the edge of either a great hope for this planet or a terrible disaster—perhaps for two species. Civilization is a reality. You're a biologist. You know the mechanics of natural selection. Capabilities don't evolve in excess of needs. How could a carnivorous felinoid get enough brain for space travel? That's not how evolution works." That was a point, certainly. But there was an answer to it:

"How could an omnivorous savanna-dwelling ape get enough brain for space travel? That's surely equally impossible."

I felt vibration through the floor. Another big ship taking off. They were lifting heavy material. From my window I could see construction crews at work on hilltops beyond the city, erecting new launching lasers built from old plans. We were moving now, and by all accounts the Belters of the Serpent Swarm were moving faster.

"The unions are behaving very shortsightedly," he went on, "A lot of their leadership sees the rearmament program simply in terms of more labor demand and more wages and so are supporting it. I think they're in for a rude shock. Do you know what a bayonet is?"

"I do now."

"It was described centuries ago as an instrument with a worker at each end. Even capitalists like Diderachs and the Herrenmanner should see the point: money spent on production repays itself and perhaps more; Money spent on armaments may give employment but in the long run it's wasted."

It's a lot to think about," I said. I wasn't lying. The cetaceans that mankind had once hunted and experimented upon and drowned wholesale in driftnets were now trading partners and friends. There were pods of dolphins breeding in one of our smaller enclosed seas, arrivals on the last and biggest slowboat, waiting till their numbers and the numbers of Earth fish grew and they took possession of Wunderland's oceans.

"Think fast. We may not have much time."

I knew I wasn't going to get much sleep again that night. Pills, I knew by too much recent experience, would only make me groggy the next day, and the doc wouldn't dispense anything stronger without better reasons than I could give it. I called Dimity after a few hours, using a selector so I would not wake her if she was asleep. She wasn't.

I told her my major concern and hope: that a spacefaring race had to be peaceful. This was not a matter entirely of wishful thinking but also of the logic of technology and education. Cooperation and peace were needed to create cultures that could support the knowledge industries—the stable governments, the institutes and universities, the individual dreamers and inventors, and the workshops and factories, as well as the surplus of wealth—that made space flight eventually possible.

"Have you heard of the Chatham Islands on Earth?" she asked.

"Vaguely."

"In the Pacific, off New Zealand. Very late in pre-space-flight history, in the nineteenth century, a shipload of Maoris got there and ate the inhabitants. The old Maori war canoes had never gone that way, so the islanders had been left in peace. But these Maoris stole a European sailing ship and its charts."

I see. Stolen technology."

"Think of the ancient Roman Empire. Or the ancient Chinese."

"I don't know much about them."

"Very low tech, but in their way great achievements. They were built up, one way or another, in periods of relative peace and order. Then savage barbarians came: but they didn't destroy them, they took them over.

"Indeed the Romans themselves seem to have been primitives who took over the heritages of the Greeks and Etruscans, so that you suddenly had a warrior culture, disciplined and armed and organized at a level far beyond anything it could have achieved on its own.

"Human history is full of such cases if you look: technology taken from somewhere else. The point is, human culture or civilization and technology have often been out of step. For all we know, this may be the same thing, on a bigger scale."

"For all we know... We have so little evidence of anything." I repeated van Roberts's words: "Civilization is a reality."

"We wouldn't be the first... Egyptians, Babylonians, Greeks, Romans... They all had civilization as a reality. Where are they now? I'm only saying it's a possibility that these creatures are out of whack too. I wonder how the Chatham Islanders felt when they saw the clipper ship.

But that's something we'll never know."

"I hope you're right about that last bit."

Chapter 7

It's reasoning that ruins people at the critical hours of their history.

—Pierre Daninos

"You know, Professor," said Kristin von Diderachs, "there's an aspect of all this we haven't fully considered. These aliens may be an opportunity as well as a threat."

"You've no doubt they are real?" I had been doing another broadcast for the Defense Council. The contents of the script I had been given were reassuring and optimistic, but I was tired and did not feel reassured.

"No. Whatever van Roberts and his merry band of cranks and radicals may say, we didn't fake those transmissions or anything else. And between you and me, I understand things are happening in space already. But even setting that aside, surely you can see that we are treating them as a genuine warning. What else have we all been sweating over? Do they think we want a high-tax regime?"

Possibly. If it keeps them down."

"Nonsense. We pay more tax than they do. And how can it help us to increase popular discontent? Have you any idea what the costs have been already?"

"I think I've got some idea."

"I doubt it. Practically every aspect of industrial production has been disrupted. War production helps create an illusion of prosperity but in the long run it's money thrown away. We are treating these aliens as potential enemies because it's the sensible thing to do. But there's a chance they are not enemies. We should meet them—as far out in space as we can travel—and negotiate. I know there are people in Sol System thinking along the same lines. They've sent us accounts of negotiating games they've set up."

How useful are they?"

"They are putting a lot of thought into them. Think what the cats could teach us!"

"Oddly enough, I have been thinking a bit along those lines. So have some other people."

That could be hopeful. They could be a big positive influence for order and stability. And order is what we need at the moment. Human occupation of this planet is still vulnerable."

"I'm well aware of it."

"This could give us a chance to work together."

"You mean that in times of crisis people turn to the certain things?"

"Well, yes, partly that. But what I really meant was that... these outsiders could be allies."

I don't see... "

"You don't build spaceships without cooperation. That means you don't build them without respect for ideals of order and discipline. Somebody has to give the orders. I've studied Earth history. Would the Greek democracies have got into space? No, they spent all their time squabbling among each other until the Romans took them over and organized them. Remember Shakespeare: 'Take but degree away, untune that string, And, hark, what discord follows!' That's a universal truth. If they have space travel they have a scientific civilization, and that means a class-based civilization."

"I certainly hadn't seen it that way before."

"The defense preparations are obviously necessary, but for more reasons than one. The Prolevolk leaders aren't all wrong in their appreciation of the situation. Things are starting to break up here. They've got to be set to rights. I'm telling you this so you'll know who to side with when the time comes—if it comes. "I've studied and thought about history. When the ancient explorers on Earth discovered a new country, it was the people in control they naturally allied with. When Europeans reached the Pacific islands it was the local kings they went to. If the Polynesian kings played their cards sensibly, they could do all right. I've been studying the records. The kingship of Tonga goes on today; there is still a Maori aristocracy and a restored monarchy of an old line. We could learn from their experience, and last longer, perhaps become stronger than ever. If we handle these newcomers properly and have them for friends."

They kill people. I've seen the bones."

"Possibly there have been unfortunate incidents. Tragic incidents. After all, if the creature allegedly seen near the monastery was the same species as were on the Angel's Pencil, they may have reason to approach us warily. The behavior of the Angel's Pencil has rather committed us to a certain situation."

Yes, I suppose so."

"And after all, can we know what really happened? Who attacked first? They have to be something like us... don't they?"

"I don't know." It was an argument that had been going on in my own head ceaselessly. Reason said yes, something else said no. I brushed him off and got into my car.

Six weeks had passed. The most obvious change had been the number of ships taking off from the München spaceport around the clock and the number that seemed to land by night. But there were other changes too. We seemed to know as little about keeping security as we did about anything else military. Everybody knew. But there was a strange taboo about speaking of it.

There were new looks on the faces in the München streets, everything from excitement to haunted terror. There were people who walked differently, and people who looked at the sky. There were a couple of ground-traffic snarls, and no one seemed to be attending to them. The Müncheners stuck to some old-fashioned ways, including one or two cops on foot with the crowds. Not this evening, though. The police seemed to be somewhere else.

There were also, I noticed, people lining up at certain shops. Food shops mainly, but sporting goods, hardware, camping, car parts and others as well. I had not seen that before except at the Christmas–New Year's sales.

That reminded me of something else, and I took a detour past St. Joachim's Cathedral. Its imposing main doors were normally shut except when Christmas and Easter produced more than a handful of worshipers. Its day-to-day congregation, such as it was, went in and out through a small side door. Now the main doors were open, and there seemed to be a number of people going up the steps. There were also some new street stalls set up near the cathedral, and they seemed to be drawing a crowd, too. I stopped to investigate, and found they were peddling lucky charms, amulets and spells.

"This is the plan for something called a Bofors gun. From the twentieth century. One of the Families boasted an eccentric collector who brought it as a souvenir of Swedish industry. It fires exploding shells, but we have calculated that shells loaded to this formula wouldn't damage even the material of a modern car, let alone what we might expect of enemy armor."

"So?"

"We're building it anyway. At least we have the plans and drawings, and we've modernized it as much as we can. We've strengthened the barrel, breech and other mechanisms and hope they'll take modern propellants without blowing apart. We've rebuilt something from the old plans called a sabot round that may pierce very strong material. We've been able to speed up the loading too, and of course we have better radars and computers for aiming. We'll put modern mining explosive and depleted uranium in the shells and hope for the best."

"It looks slow."

"We're linking it with modern radar and computers and powering up the traverse. For a long time the tendency in war seems to have been more speed with everything. But that comes to a plateau. It may be different in space with decisions being made electronically, but infantry fighting can only get just so fast. Even with every electronic enhancement, it seems human beings—and I hope others—have some sort of limit to the speed with which they can make complicated battlefield decisions. And of course it may be that you're often fighting without electronics.

"Further, your own speed can become a weapon against you: run into something too fast and your speed exacerbates the impact. Also you lose control. That's the theory, anyway. At the moment theory is all we've got. The same collection as gave us the Bofors gun gave us this—it's called a Lewis gun. Not as powerful or as futuristic as it looks, but it's quick and simple to make.

"There's something else called a Gatling gun. We were very puzzled by the descriptions until we realized they referred to two guns with the same name, about 120 years apart."

"The later is likely to be the better."

/>

"Well, we're trying to build the one we've got some drawings of. We're not sure which one it is."

"There's another message from Sol System," said Grotius. He was wearing new clothes now, a gray outfit with an old-fashioned cap and badges at the collar and shoulders. An archaic concept called a "uniform," meant to make hierarchy obvious and facilitate decision-making and enforcement. Several other Defense Committee folk were wearing them too, chiefly Herrenmanner.

"There's been more trouble. Scientific vessels, ferries to the colonies, robot explorers, have just stopped transmitting. There was still no full public announcement on Earth when this message was sent, but of course they've got ARM to organize things. They let us know so we can do what we 'think best.' They've reminded us about the Meteor Guard and its weapons potential, as though we hadn't thought of that for ourselves. Telling us doesn't compromise ARM's precious security."

"Decent of them." We "Star-born" had a somewhat patronizing attitude to the flatlanders of Earth—to all Sol Systemers in fact—but I had never heard them spoken of with such bitterness and anger before. "If they'd told us a couple of months ago it might have been useful."

"ARM has useful inventions suppressed long ago that they could tell us about. It's like the Roman emperors reputed last message to Britain as the legions withdrew to defend the Roman heartland: 'The cantons should take steps to defend themselves.' That means: 'Good-bye and good luck!' for those of you who aren't ancient historians."

The Integral Trees - Omnibus

The Integral Trees - Omnibus A World Out of Time

A World Out of Time Crashlander

Crashlander The World of Ptavvs

The World of Ptavvs Ringworld

Ringworld Juggler of Worlds

Juggler of Worlds The Ringworld Throne

The Ringworld Throne The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic

The Magic Goes Away Collection: The Magic Goes Away/The Magic May Return/More Magic A Gift From Earth

A Gift From Earth Escape From Hell

Escape From Hell Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VII Rainbow Mars

Rainbow Mars Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - V Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - I Destroyer of Worlds

Destroyer of Worlds Man-Kzin Wars XIV

Man-Kzin Wars XIV Treasure Planet

Treasure Planet N-Space

N-Space Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition

Man-Kzin Wars 25th Anniversary Edition The Ringworld Engineers

The Ringworld Engineers Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XII The Magic May Return

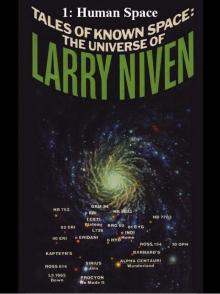

The Magic May Return Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven

Tales of Known Space: The Universe of Larry Niven The Magic Goes Away

The Magic Goes Away Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - VI Man-Kzin Wars III

Man-Kzin Wars III Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XI Inferno

Inferno 01-Human Space

01-Human Space Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIV The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton

The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton Ringworld's Children

Ringworld's Children Man-Kzin Wars XII

Man-Kzin Wars XII Scatterbrain

Scatterbrain Man-Kzin Wars 9

Man-Kzin Wars 9 Man-Kzin Wars XIII

Man-Kzin Wars XIII Flatlander

Flatlander Man-Kzin Wars V

Man-Kzin Wars V Destiny's Forge

Destiny's Forge Scatterbrain (2003) SSC

Scatterbrain (2003) SSC The Time of the Warlock

The Time of the Warlock Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II

Larry Niven's Man-Kzin Wars II Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9)

Man-Kzin Wars IX (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 9) Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8)

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 8) Treasure Planet - eARC

Treasure Planet - eARC The Draco Tavern

The Draco Tavern Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - The Houses of the Kzinti The Fourth Profession

The Fourth Profession Betrayer of Worlds

Betrayer of Worlds Convergent Series

Convergent Series Starborn and Godsons

Starborn and Godsons Protector

Protector Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - IV Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4)

Man-Kzin Wars IV (Man-Kzin Wars Series Book 4) The Legacy of Heorot

The Legacy of Heorot 03-Flatlander

03-Flatlander Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII

Larry Niven’s Man-Kzin Wars - XIII Destiny's Road

Destiny's Road Fate of Worlds

Fate of Worlds Beowulf's Children

Beowulf's Children 04-Protector

04-Protector The Flight of the Horse

The Flight of the Horse Man-Kzin Wars IV

Man-Kzin Wars IV The Moon Maze Game dp-4

The Moon Maze Game dp-4 The California Voodoo Game dp-3

The California Voodoo Game dp-3 07-Beowulf Shaeffer

07-Beowulf Shaeffer Ringworld's Children r-4

Ringworld's Children r-4 The Man-Kzin Wars 05

The Man-Kzin Wars 05 The Man-Kzin Wars 12

The Man-Kzin Wars 12 Lucifer's Hammer

Lucifer's Hammer The Seascape Tattoo

The Seascape Tattoo The Moon Maze Game

The Moon Maze Game Man-Kzin Wars IX

Man-Kzin Wars IX All The Myriad Ways

All The Myriad Ways More Magic

More Magic 02-World of Ptavvs

02-World of Ptavvs ARM

ARM The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld)

The Ringworld Engineers (ringworld) Burning Tower

Burning Tower The Man-Kzin Wars 06

The Man-Kzin Wars 06 The Man-Kzin Wars 03

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC

Man-Kzin Wars XIII-ARC The Hole Man

The Hole Man The Warriors mw-1

The Warriors mw-1 The Houses of the Kzinti

The Houses of the Kzinti The Man-Kzin Wars 07

The Man-Kzin Wars 07 The Man-Kzin Wars 02

The Man-Kzin Wars 02 The Burning City

The Burning City At the Core

At the Core The Trellis

The Trellis The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 mw-1 The Man-Kzin Wars 04

The Man-Kzin Wars 04 The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names

The Man-Kzin Wars 08 - Choosing Names Dream Park

Dream Park How the Heroes Die

How the Heroes Die Oath of Fealty

Oath of Fealty The Smoke Ring t-2

The Smoke Ring t-2 06-Known Space

06-Known Space Destiny's Road h-3

Destiny's Road h-3 Flash crowd

Flash crowd The Man-Kzin Wars 11

The Man-Kzin Wars 11 The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014

The Best of Galaxy’s Edge 2013-2014 The Ringworld Throne r-3

The Ringworld Throne r-3 A Kind of Murder

A Kind of Murder The Barsoom Project dp-2

The Barsoom Project dp-2 Building Harlequin’s Moon

Building Harlequin’s Moon The Gripping Hand

The Gripping Hand The Leagacy of Heorot

The Leagacy of Heorot Red Tide

Red Tide Choosing Names mw-8

Choosing Names mw-8 Inconstant Moon

Inconstant Moon The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War

The Man-Kzin Wars 10 - The Wunder War Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld

Fate of Worlds: Return From the Ringworld Ringworld r-1

Ringworld r-1 05-A Gift From Earth

05-A Gift From Earth The Integral Trees t-1

The Integral Trees t-1 Footfall

Footfall The Mote In God's Eye

The Mote In God's Eye Achilles choice

Achilles choice The Man-Kzin Wars 01

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 Procrustes

Procrustes The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3

The Man-Kzin Wars 03 mw-3 The Goliath Stone

The Goliath Stone The Man-Kzin Wars 09

The Man-Kzin Wars 09